What is it that feeds our battle, yet starves our victory?

Speaker Johnson: A Reminder.

And MTG is there to help make it stick.

January 6 tapes. A good start…but then nothing.

Were you just hoping we’d be distracted by the first set and not notice?

Are you THAT kind of “Republican”?

Are you Kevin McCarthy lite?

What are you waiting for?

I have a personal interest in this issue.

And if you aren’t…what the hell is wrong with you?

Fun Quote

(HT Aubergine)

This is amazing. This is glorious. Summon a surgeon – it’s been a little over a week and you’re supposed to call the doctor after just four hours.

From Kurt Schlichter, who can certainly write a good rant (https://townhall.com/columnists/kurtschlichter/2025/01/30/trumps-winning-streak-is-totally-discombobulating-the-democrats-n2651308)

Yep, Kurt has noticed that lots of people are getting twanging schadenböners.

And you do not have to be male to get this kind of böner.

Lawyer Appeasement Section

OK now for the fine print.

This is the WQTH Daily Thread. You know the drill. There’s no Poltical correctness, but civility is a requirement. There are Important Guidelines, here, with an addendum on 20191110.

We have a new board – called The U Tree – where people can take each other to the woodshed without fear of censorship or moderation.

And remember Wheatie’s Rules:

1. No food fights

2. No running with scissors.

3. If you bring snacks, bring enough for everyone.

4. Zeroth rule of gun safety: Don’t let the government get your guns.

5. Rule one of gun safety: The gun is always loaded.

5a. If you actually want the gun to be loaded, like because you’re checking out a bump in the night, then it’s empty.

6. Rule two of gun safety: Never point the gun at anything you’re not willing to destroy.

7. Rule three: Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire.

8. Rule the fourth: Be sure of your target and what is behind it.

(Hmm a few extras seem to have crept in.)

Spot (i.e., paper) Prices

Last week:

Gold $2,771.70

Silver $30.64

Platinum $957.00

Palladium $1,008.00

Rhodium $5,000.00

FRNSI* 133.081-

Gold:Silver 90.460+

This week, 3PM Mountain Time, Kitco “ask” prices. Markets have closed for the weekend.

Gold $2,801.20

Silver $31.27

Platinum $989.00

Palladium $1,036.00

Rhodium $5,000.00

FRNSI* 134.508+

Gold:Silver 89.581+

Gold zig-zagged across the 2,800 mark (which is record territory) on Friday. Since most people quote bid, not ask, and the bid for gold is 2799.20 you might hear that it closed just short of $2,800 on Friday. (I quote ask, because that’s the buyer’s price and you should be buying, right?) Gold was even above 2,810 at least once on Friday.

Of course this means that the FRNSI is at an all-time high.

Silver, on the other hand, actually dropped on Friday but still up nicely for the week as a whole. At least the gold/silver ratio has dropped a bit.

*The SteveInCO Federal Reserve Note Suckage Index (FRNSI) is a measure of how much the dollar has inflated. It’s the ratio of the current price of gold, to the number of dollars an ounce of fine gold made up when the dollar was defined as 25.8 grains of 0.900 gold. That worked out to an ounce being $20.67+71/387 of a cent. (Note gold wasn’t worth this much back then, thus much gold was $20.67 71/387ths. It’s a subtle distinction. One ounce of gold wasn’t worth $20.67 back then, it was $20.67.) Once this ratio is computed, 1 is subtracted from it so that the number is zero when the dollar is at its proper value, indicating zero suckage.

It is a CULT

Admittedly, the channel I am about to point you to–a brand new one–has one big Dufus Factor involved and that is the silly mask the guy wears for some reason having to do with his other gaming channel.

But when talking about Flat Earth he is spot-on. (And I’ve seen serious content delivered by people in sillier costumes–e.g., dinosaurs.) And…hallellujah! Except for two interviews his videos are short! Anyhow, his comparison of Flat Earth and cults seems spot on.

Nathan Oakley (as in “where are the GUNS, Nathan?!?!?”) tried to respond but of course was selective. As Oakley is credibly alleged to be a child abuser I won’t give him a link (you can surely find it if you want), but the response to his response is here.

CyberWaffle also has a response to the claims that The Final Experiment was done in a studio. Apparently he has some experience with the movie industry.

(In a later video he says he got the cost wrong…it should be 26 billion dollars.)

There seem to be four distinct responses to the Final Experiment from Flat Earthers (based on the interview with MC Toon).

- Some maintain it doesn’t matter. “We never made a claim.” Well you still have to be able to explain what was seen.

- Some retroactively claim that they were able to predict a 24 hour sun (this is revisionism (i.e., bare faced lying); there are plenty of videos of big-name Flerfers saying they would like to go to Antarctica during Austral summer, see the sun set, and thus prove the globe wrong–they didn’t erase them fast enough). But now they’re claiming that the Sun they saw was a reflection off the dome. (Decisively disproven by sunspot photos.)

- One pastor claims the Sun was actually Satan.

- But the most common claim is that it was faked; apparently “Flat Earth Dave [Weiss]” (who originally stood up against claims of “greenscreen”) has been brought back into line.

The problem is, they took plenty of videos not yet released to show it wasn’t a fake. Claims it was in a 360 degree surround studio are exploded by a drone flight to about a mile AGL (above ground level), a video that has been released. No studio could be that tall; that’s much taller than any building we have ever built.

MC Toon points out that anyone can go, but clearly the great expense (the Final Experiment cost $31K per participant) is a barrier. He has a standing offer to anyone who thinks it was fake. He will put $100,000 in escrow; they can do the same. Then they go together. Whoever’s right about the Sun gets the money. If they get turned away at gun point the Flerfer gets the money. None of them are confident enough in their position to have taken him up on it. (If they were that confident but poor, they could borrow the money for the trip and the 100K fully confident that they will have $200K afterwards to pay off the $131K loan with. Though perhaps a bank will laugh in their face when they make the application and explain why they are going.)

The Final Experiment team tried to anticipate every possible way that Flerfs could deny they had done what they did. As CyberWaffle put it: “That’s the only really bizarre thing about this trip to Antarctica, where the whole purpose of the trip to Antarctica, the whole time….no one’s ever done an expedition on the pure purpose to have to prove that they did the expedition.”

Here’s an Interview with MC “Where are the GUNS Nathan” Toon. Pay especial attention from 50:36 on and then at 58:00 (though if you have time the whole thing is worth watching).

Another; his most recent (unless he releases one between now (Thursday) and Saturday). This one lays out the best why I harp on this. Flat Earth isn’t just wrong, which is bad enough, it is harmful to the people who believe it. As often as not they lose their friends and even alienate their families.

But here’s a final one, from a totally different source. This one makes a larger philosophical point, and is an interesting exposition on the subject of “respecting one’s elders.”

[Edit to add: This last video’s conclusion could be taken as implying that we should, for instance believe the medical establishment. Maybe he actually does mean that. But I’ll go so far as to say that sometimes the experts disagree with each other and we do have experts on our side in this case. And the “establishment” has plenty of motivation to warp its judgement. That’s quite a different situation than disagreeing with your mechanic.]

CyberWaffle sometimes talks disparagingly of “conspiracy theories” and, in the way he understands the term, he is right to do so. The classic conspiracy theory is impossible to argue with, not because it is true, but because the holder of the theory is primed to dismiss any contrary evidence as faked or a lie, as part of the cover up.

The sorts of things we discuss here are (almost entirely) not like that. We bring a lot here, and so far as I know, if someone were to actually bring contradictory evidence the response here would not be to shove fingers in ears, shake our heads and say “nuh-uh!”

On the other hand, if you ever get to that point of wanting to simply dismiss any counter-evidence as fake, then you’re in danger of disconnecting from reality–in the unlikely event that you haven’t already done so.

That’s a very bad place to be. As Ayn Rand once said (and I’m paraphrasing), one is free to evade reality, but one cannot evade the consequences of evading reality.

And sometimes the consequences may be fatal.

More On Geology

The Geologic Timescale

The same Kurt Schlichter article I quoted at the top since Aubergine couldn’t resist calling out the schadenböner reference, has this line (earlier in the same paragraph):

We have more energy than the freshly unleashed Permian Basin.

What is this “Permian Basin”? As it happens there are two of them, one centered on the North Sea in Europe (remember a lot of oil comes from offshore rigs in the North Sea), and the other is the one in West Texas and southeast New Mexico.

If you type “Permian Basin” into Wikipedia, you go to a page that tells you this, and you can then select the one you’re interested in. It also mentions that neither of them are in Perm Krai.

What on Earth is “Perm Krai”? Perm Krai does not have a link (but should). A “krai” (край, plural края́) turns out to be “one of the types of federal subjects of modern Russia, and was a type of geographical administrative division in the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR.” A krai was traditionally a far out, peripheral frontier area (in fact it’s etymologically related to the word “Ukraine”), while an oblast was a bit more central. In today’s Russian Federation there’s no functional difference between a krai and an oblast; a subdivision of Russia is one or the other based on tradition. (Russia also has other kinds of subdivisions: republics, cities of federal significance, an autonomous oblast, and autonomous okrugs. All have equal status as constituent entities of the Russian Federation according to Article 5 of the Constitution of Russia.)

So here’s a map–which unfortunately lost its labeling on the way over from Wikipoo:

In green are “Republics” which have a little more autonomy (the biggest one is Sakha, better known as Yakutsk to Risk players, and is the largest territorial subdivision in the world). Orange are krais, yellow are oblasts, red are the two federal cities (Moscow and St. Petersburg; Sevastapol in Crimea is also a federal city but most nations do not recognize Russian ownership of that or the four Ukrainian oblasts recently annexed from Ukraine [in cross-hatch at the left side of the map]). The one autonomous oblast in in purple, four autonomous okrugs in blue.

Getting back to our subject, Perm Krai is here, tucked up against the Ural Mountains on the west side. (The Ural Mountains form the traditional border between Europe and Asia, since they aren’t really separate continents. The eastern border of Perm Krai is part of that dividing line.)

Perm has its own coat of arms (just like every “Federal Subject” does):

Despite being deep inside Russia, Perm Krai has a significant population of ethnic minorities; some are not ones you’re likely to have heard of, though: Tatars and Ukrainians, Komi-Permyaks, and Bashkirs. Bashkirs are actually Turkic, but the Komi-Permyaks…well, they’re “Uralic” meaning their closest well-known relatives are the Finns and Hungarians. Its largest city is named…Perm (it gave its name to the Krai), with just a bit over a million people. The total population is roughly 2.5 million, down from 3 million when the Soviet Union collapsed.

OK…so that was (maybe) interesting and even has a tiny bit to do with current events, but…why on Earth is an energy-rich place in Texas and New Mexico named for this place?

SO glad you asked!

The Geologic Timescale Today

I struggled with this topic a bit. Trying to just talk about it historically is hard, because a lot of what I am reading assumes you know what we know today. And a lot of this topic is naming conventions and historic holdovers, but a lot is not. If I were to try to trace this from the beginning without some context, it would get a bit confusing. which is unsatisfactory. So I’m going to briefly outline the modern picture, then jump back and try (and likely fail) to explain how we got here. That might be more confusing, but I aim to excel.

The geologic timescale as we know it today is our best effort to order the different rocks we find around the Earth, by time; and since this is science things need to be classified in buckets so that we can see patterns that will help illuminate what is going on.

This is a vast topic so it gets subdivided. In fact it gets sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-subdivided; there are six “levels” of subdividedness (if that wasn’t a word before, it is now); generically referred to as “units.” Except that there are two different names for the levels. When considering the rocks themselves, they are “chronostratigraphic units,” when talking about the times, they are “geochronologic units.” However when we get to looking at specific ones, they have the same names. Thus “Permian” refers to both a chronostratigraphic unit and a geochronologic unit.

The entire history of the Earth is first subdivided into eons (geochronologic, time) which are each equivalent to eonothems (chronostratigraphic; rock layers). There are four of these according to the standard scheme. In order, newest to oldest (newest is always at the top, because it mimics the principle of superposition, they are:

- Phanerozoic (the current eon/eonthem)

- Proterozoic

- Archean

- Hadean (starts with the formation of the Earth)

As you might imagine, the older, the less well understood. Thus, the Hadean is not further subdivided; we have almost nothing to work from with this one. The other three eons are subdivided into eras (geochronologic; time) or erathems (chronostratigraphic; actual rock layers). There are ten defined eras, from oldest to newest these are: The Eoarchean, Paleoarchean, Mesoarchean, Neoarchean, Paleoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic, Neoproterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. As you likely guessed, the first four are subdivision of the Archean, the next three of the Proterozoic, and the final three by elimination are subdivisions of the Phanerozoic; we are living in the Cenozoic era, with rocks being laid down now part of the Cenozoic erathem. To summarize:

- Phanerozoic (the current eon/eonthem)

- Cenozoic (the current era/erathem)

- Mesozoic

- Paleozoic

- Proterozoic

- Neoproterozoic

- Mesoproterozoic

- Paleoproterozoic

- Archean

- Neoarchean

- Mesoarchean

- Paleoarchean

- Eoarchean

- Hadean (starts with the formation of the Earth)

The eras that are part of the Proterozoic and Phanerozoic (the Archean and certainly the Hadean are not subdivided to this level) are further subdivided into periods (geochronologically, time) equivalent to systems (chronostratigraphic, rock layers); there are 22 of these. You may recognize some of these names, but the ones from the Proterozoic eon/eonthem are new. I won’t be mentioning these much; the last two, however are the Cryogenian and Ediacaran. Once you get into the Phanerozoic, though, the Paleozoic is subdivided (oldest to newest) into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous (which is a special case, there are two sub-periods of it called the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian), and Permian, and I will be talking about these. (In particular if I don’t discuss the Permian after that intro, someone will probably put a price on my head.) The Mesozoic is subdivided into the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous. (If you have never heard of the Jurassic, you’ve been living under a rock. Maybe even one that formed in the Jurassic.) The Cenozoic is subdivided into the Paleogene, Neogene and Quaternary periods (or systems). [Note: the Cenozoic was reorganized in 2008 [edit]. Before then used to be a period called the “Tertiary” instead of the Paleogene and Neogene.] We are living in the Quaternary period; rocks laid down now are part of the Quaternary system.

- Phanerozoic (the current eon/eonthem)

- Cenozoic (the current era/erathem)

- Quaternary

- Neogene

- Paleogene

- Mesozoic

- Cretaceous

- Jurrasic

- Triassic

- Paleozoic

- Permian

- Carboniferous (Mississippian + Pennsylvanian)

- Devonian

- Silurian

- Orodivician

- Cambrian

- Cenozoic (the current era/erathem)

- Proterozoic

- Neoproterozoic

- Ediacaran

- Cryogenian

- Tonian

- Mesoproterozoic

- 3 periods

- Paleoproterozoic

- 4 periods

- Neoproterozoic

- Archean

- Neoarchean

- Mesoarchean

- Paleoarchean

- Eoarchean

- Hadean (starts with the formation of the Earth)

That’s three levels, and that’s as deep as I am likely to get. However, you should remember there are finer gradations, the epoch/series, the subepoch/subseries, and the age/stage (giving the “time” name first, then the “rock” name second). These exist because there’s really no situation where a single distinct rock layer covers an entire period.

I’m certainly not expecting you to remember these last three levels. I certainly won’t. But please be aware that they are there. The systems (hence periods) were often originally built up by combining series (epochs).

(However, even popular treatments will break the Cenozoic down one more level than this down to the epoch level, and all of those have names ending in -cene. None, fortunately were named after the Russian river Ob.)

In some cases which smaller units got grouped into which larger units is arbitrary, but in other cases it’s anything but. There are clear, obvious dividing lines between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, as well as between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic; as we will see there was a mass extinction event at both of those dividing lines. Other, lesser mass extinctions turn out to be boundaries between periods/systems.

One more thing to add: For historic reasons, the first three entire eons put together are sometimes informally called “the Precambrian,” almost as if they were only as important as a mere period (two levels below them in the schema). This is largely due to the fact that until recently we knew next to nothing about those three eons and had a hard time distinguishing them from each other in any case. It was just some indefinitely long time.

The whole schema as it exists today (and with some text about proposed changes) is laid out in painstaking detail here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geologic_time_scale, broken down all the way to Ages where such subdividing has been done.

Which brings us to the question of how we tell these apart from each other (and why those methods failed, at first, with the Precambrian). And so now I will switch to the historical perspective. So tuck all of that away in the back of your minds, wipe the mental slate temporarily, and…here we go.

Historical Development

Back to the late 18th and early 19th century, where we start to see the development of the geologic timescale. Between mining and the coal industry that was firing up to support the Industrial Revolution, geologists started to realize the fossils could tell us a few things. Similar fossils would appear at the same places in a bottom-to-top sequence and they could often be used to establish that the rocks were of a specific age. William Smith could distinguish otherwise-similar formations (i.e, rocks of the same color and texture) based on what fossils appeared in them. Putting things together people like Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brogniart realized you could set up a complete sequence of rocks, oldest to youngest, based on index fossils. Index fossils are fossils that were widely distributed (hence could be seen in large parts of the globe) and existed briefly, so they’d be confined to one stratum.

When they published in 1811, we saw the birth of modern stratigraphy. We started to see what today we consider the systems/periods within the Phanerozoic.

(Cuvier, by the way, used the sequence to argue for catastrophism. This means multiple disasters–not just one, that caused many of the different abrupt boundaries in the geologic column. And you know what…he wasn’t completely wrong, though it took some time for this to be recognized.)

Note that not every kind of fossil is an index fossil. A good candidate for an index fossil will be something that lived in the oceans (hence was probably nearly global) and doesn’t appear across a long span of time. The narrower the time, the more precisely you can date a formation.

Because fossils were used to distinguish epochs and periods from each other, we really could only get anything useful from a certain time onwards. Before that time the rocks apparently had no fossils in them (we know now this is not quite true). After that time…we have fossils.

This was a very iterative process, with people noting strata and their relationships slowly and a big picture emerging at last. In many cases the epochs were noted first and combined into the periods later; with some re-groupings along the way. So here’s what we ended up with, listed from oldest to youngest, and not by any means in the order they were discovered or got their final names.

English geologists were particularly prolific, identifying the following periods (from oldest to youngest): the Cambrian (from Cambria, meaning Wales), in 1835; the Ordivician (from a Celtic tribe) in 1879; the Silurian (another Celtic tribe) in the early 1830s; the Devonian (named after Devon, England) also in the 1830s, and the Carboniferous (named after the coal) in 1811. Anything older than the Cambrian at the time appeared to have no fossils in it, and as mentioned earlier just got called the “Precambrian”. These periods are abbreviated, respectively, Ꞓ, O, S, D, and C.

In North America, the Carboniferous period was initially treated as two periods, the Mississippian (older) and Pennsylvanian (younger)…so America does make its way into the schema. This kind of monkeywrenched the scheme when one group of geologists talked about the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian and the other talked of the Carboniferous. The compromise eventually arrived at is to consider this period, and only this period, as consisting of sub-periods by those names. Other periods don’t have sub-periods but go directly to being divided into epochs.

(That wasn’t the only dispute by any means. As you might have noticed, the Ordovician was first named much later than the others, and was created by reorganizing what we had before, as a way to settle a different argument altogether.)

England certainly has newer rocks than the Carboniferous, but for whatever reason other countries beat England to the punch as far as identifying and naming more recent periods.

The very next period, the Permian (P), was found in the Ural mountains of Russia and added to the scheme in 1841–and this is how the Permian basin of Texas got its name. It turns out to consist of rocks from the same period. (Famous fossils from the Permian include a lot of corals [an entire reef nows form the Gaudalupe mountains in West Texas] and Dimetrodon, the sail-back lizards, which contrary to popular belief were not dinosaurs.)

(As for how a coral reef ended up way out in West Texas at elevations up to 8751 feet…well, that’s for a future post.)

The next one after that was the Triassic (T), first noted in Southern Germany. This was in turn composed of three rock layers (hence the “tri” in the name). It got that name in 1834, however it had been noted earlier than that.

In the Jura mountains of France and Switzerland, we found the Jurassic (J). This was a markedly earlier discovery from 1795.

The Cretaceous was first identified in the Paris basin in 1822 and the name comes from the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate from the shells of microscopic sea organisms). Its abbreviation is K, not C, from German Kreide, chalk.

Next was the Tertiary. Those rocks are quite new (as such things are measured); it brings us almost to the present day. This name actually goes back to the middle 1700s and Arduino, who divided geologic time into primitive, secondary, and tertiary periods based on what he saw in Northern Italy, so the Tertiary was essentially discovered in Northern Italy. For a time, this period was identified has having been laid down during the Flood.

The Tertiary is now considered obsolete and has been broken up into two periods, the Paleogene (Pg) and Neogene (N). I know that the Tertiary used to be abbreviated T, but that means the Triassic must have had a different abbreviation back then. This relatively recent rearrangement was very controversial and part of the dispute was what to do about the very next (and latest) period…

The Quaternary, which was named such because it followed the Tertiary. It was first identified by Arduino in 1759 (by contrast with the Tertiary) and very nearly didn’t survive the recent reorganization of the Tertiary; it almost got folded into the Neogene. This is the latest period/system.

These periods were (and still are) grouped into three Eras, with the Cambrian through Permian making up the Paleozoic (“old life”) era, the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous making up the Mesozoic (“middle life”) era, and the Tertiary and Quaternary making up the Cenozoic (“new life”) era.

Anything before the Cambrian got lumped together as the “Precambrian.” There were no index fossils in those rocks (at least we didn’t think so at the time), so although we could look at the rocks at one location and do relative dating on them, we couldn’t correlate the Precambrian rock layers in one location with those in another location far away.

Eventually we would overcome this and build up the much more refined timescale we have today, but for a long time the Precambrian was an difficult-to-chart wasteland of geologic time.

Geologists worked on and after two centuries of development, we have today’s schema.

As a reminder, today the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras are in turn grouped together into the “Phanerozoic Eon” and we’ve been able to subdivide the Precambrian into three full eons with some subdividing into eras and periods.

I’m going to jump ahead a bit, and talk about the Precambrian fossils that we have more recently discovered. But first, I have to bring up a basic point.

What are fossils, and what causes them?

A fossil is any preserved remains, impression or trace of past life. Usually these are preserved in rocks, but preservation in amber (a la Jurassic Park) also happens.

We actually have to distinguish different kinds of fossils. Sometimes all we have are “trace fossils.” I always found this name misleading (I’m used to other meanings of the word “trace”), but here it means such things as footprints, tracks, burrows (without any remains of the burrower), and so on…indirect evidence of the critter. Another category of fossil that goes into this bucket is “copralites.” And these are fossilized dung. (Who would have guessed that wokester brain matter existed back then?)

In many cases we have nothing more than trace fossils to identify something, or rather to identify that something existed. We can learn a few things from them, such as that the critter liked to burrow in the sediment at the bottom of a shallow sea and was of a certain size, but we won’t learn a lot.

Sometimes we have external molds. An organism is buried, decomposes, dissolves and is gone…but the void it left in the sediment is preserved as the sediment turns to rock. Sometimes sediments fill an organism’s interior and we end up with an internal mold or endocast.

Sometimes we get an impression of the creature. This can be very interesting since we might learn about skin texture. Skins usually don’t fossilize.

There are microfossils, things you need a microscope to examine. These often are of the critters themselves.

But the “classic” fossil like the skeleton you’ve seen in museums is when a buried organism’s tissues are slowly replaced by minerals coming out of solution. This is much more likely to happen if the organism is buried underwater right after it dies and as you might imagine, that’s far more common for sea life (which is already underwater) than land life.

This turns out to be a big subject, and I am going to take the easy way out and punt you over to Wikipedia if you want to know more. (Note that on occasion a fossil is made out of iron pyrite (fool’s gold)!)

It’s much, much easier to fossilize if you have hard body parts. Skeletons, exoskeletons, shells, etc., because the other stuff is likely to decompose or otherwise be consumed by animals even when buried. The reason why “fossils show up” only in the Cambrian and later is because that’s when hard body parts first show up. (Why not earlier? My speculation: This is when predators first showed up, and critters suddenly needed body armor.)

But we do have some fossils from before the Precambrian, after all.

For instance, fossilized bacterial mats called stromatolites going clear back into the Archean, and not just the late Archean either. (These mats still exist in certain isolated places today–the situation has to be just right, however, or they get eaten before the mats can really form. Shark Bay in Western Australia is one of these places–it’s so important for that reason that UNESCO made it a World Heritage Site.) Those things that look like lumpy brown rocks are alive.

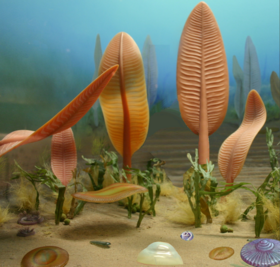

And a number of soft bodied creatures did manage to get impressions preserved in the rocks from immediately before the Cambrian; this led to the recognition, for the first time in 120 years, of a new period, the Ediacaran, named after the Ediacara Hills of South Australia, at the tail end of the Neoproterozoic era. Interestingly, many of these fossils were first noticed in England by schoolchildren, and the paleontologists around them, knowing the local surface rocks were Precambrian, dismissed their stories until one of them went with the kids and looked. These organisms look like nothing around today (unlike the Cambrian ones), and they are collectively called the “Ediacaran biota” though they only appear in the more recent part of the Ediacaran system. Here is an artist’s impression (very speculative)

And here are some pictures of the actual fossils, first charnia:

And dickinsonia.

Before that we have fossils of algae. Such as stromatolites.

Fossils versus Index Fossils

I’m going to make one more thing clear. I’ve noted that the periods were defined by index fossils..in fact in many cases the fossils actually identify epochs and ages within the periods. Completely distinct rocks in widely separated locations can be identified as being from the same epoch or age based on the index fossils they contain. The narrower the time span, the better. Not every fossil is an index fossil. Sometimes the geographic range is too small (the creature wasn’t wide spread enough) and sometimes that particular species was around for far too long.

But those non-index fossils are still confined to a certain time range, even if it’s a broad one.

Take trilobites, an entire class of creatures. (Mammals are a class. Insects are a class. Trilobites were that big a grouping.) There isn’t a single trilobite alive today. All of them lived from the middle of the Cambrian to the end of the Permian. The fossils were found in those systems so they date to those periods. (In fact the abrupt disappearance of the trilobites is one of the reasons the Permian–and the entire Paleozoic Era–is regarded as ending right then.)

We’ve identified, from fossils, 22,000 distinct species of trilobites spread out over the entire Paleozoic. There were surely many, many more. Some got to be 28 inches long. Some were scavengers, some were predators, some were filter feeders. They were an incredibly diverse and successful class. I can’t find anything to say for sure (I’m running out of time), but I would be surprised if at least some specific species of trilobites weren’t index fossils.

But you never find a trilobite after the Permian system. Never. They died out at the end of the Permian in a mass extinction, among the victims of the biggest one of all time. You can’t tell what period a generic trilobite is (though if you can identify the specific species, you have a better shot at it), but if your rock has a trilobite fossil in it, it’s Paleozoic, not Mesozoic or Cenozoic. And certainly not Precambrian.

Similarly, dinosaurs lived at characteristic times. Tyrannosaurs, for instance, are from the very end of the Cretaceous. Allosaurus and stegosaurus (and closely related species) are Jurassic. You never see these creatures outside of those ranges.

And not just for these examples, but for every species we have fossils of. This sort of precise and consistent location within the geologic column is very, very hard to explain if someone wants to claim that the entire column was laid down all at once. And this is what Young Earth Creationists claim…the whole thing was laid down in one year by the Great Flood.

But if a single flood event laid down the entire geologic column with the fossils all being things that drowned in the Flood, why would you not find drowned trilobites and tyrannosaurs and brachiosaurus and apatosaurus and pelycosaurs and ambulocetus and archaeopteryx and anomalocaris and eurypterids and camerata and ammonites and I could go on and on and on, but especially fossilized fish and gigantic Mesozoic marine reptiles of various extinct species (which could surely have held out longer) throughout the entire geological column if the whole thing happened within one year, or at least with lots of overlap? Instead we see things strictly segregated by layers. Even if you want to appeal to objects forming layers by density a) the brachiosaur bones would be in the Precambrian not the Cretaceous–in other words things didn’t sort by density and b) even if we grant for the sake of argument that they did, we’d see at least SOME cases of things not falling as far as they should because some piece of debris got in the way. Enough that we couldn’t ignore them. But we don’t. They’re segregated too perfectly by era, period and epoch. The segregation is so good because something would have to be thousands of years out of its time at the very least to end up in the wrong layer (and how would that happen? Time travel?), not just “it needed to fall for just a few more seconds to the right layer but something else blocked it.”

I’m sorry but the “all due to Noah’s Flood” claim is absurd. And this is just one line of argumentation that that is so.

Is there plenty of evidence of flooding in the geological record? Oh, yes, yes indeed, but there is no indication that it was a single event, or that any of the multitude of episodes were global. We can do relative dating on these things, after all.

(So Georges Cuvier, who as far as I can tell, believed in global catastrophes, was wrong. Or was he? Stay tuned.)

Not a Single Number?

You may have noticed that I have not given any numbers here. When were these periods? Just for instance, what’s the timespan of the Jurassic period? From when to when?

We didn’t know back then. We could look at index fossils and say that this rock from Russia was the same age as this other rock from Texas (even though from totally different formations). We could say that that rock was older than this other rock, and newer than yet a third rock. This is called relative dating. But other than crude order-of-magnitude estimates like was done with Etna, we could not do any sort of absolute dating where we could assign an actual number to the age of the rock. We could say “millions of years” or “more millions of years.” And by the way, there’s a symbol for that: Ma means “million years ago,” so 66 Ma means 66 million years ago.

How we got to absolute dating is a future topic (I might cover some other things before that). I know something about the modern methods. I have no idea (yet) how precise they were able to get before the modern methods were available, and I hope I can find out. (I may even have to walk back some of what I said in the prior paragraph if I’ve underestimated the cleverness of 19th and early 20th century paleontologists and geologists.) This is a learning experience for me too.