Were there canals in ancient Egypt?

Did ancient Egypt use canals?

Archaeological evidence for canal use is shown at many sites throughout Egypt including places such as the Giza plateau and where the Suez canal is today. The earliest written record of canal digging comes from about 3,100 BC…

Is it true that the pharaohs had a canal built?

Its origins date back to ancient Egypt.

The Egyptian Pharaoh Senusret III may have built an early canal connecting the Red Sea and the Nile River around 1850 B.C., and according to ancient sources, the Pharaoh Necho II and the Persian conqueror Darius both began and then abandoned work on a similar project.What ancient civilization used canals?

Ancient Egypt

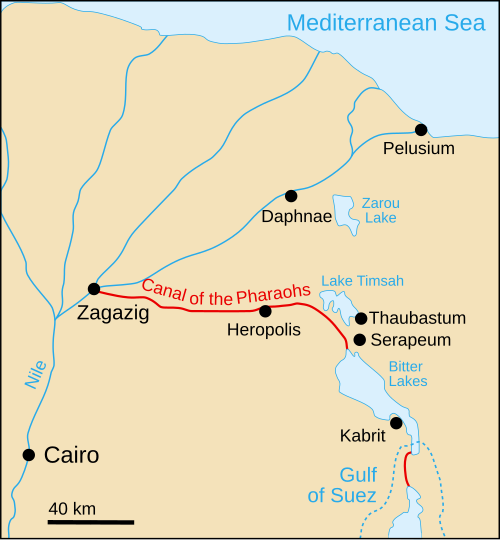

The Nile River, the lifeblood of Egypt, was utilized to create an extensive canal system for irrigation, transportation, and defense purposes. Notable canal features within ancient Egypt include: The construction of the “”Canal of the Pharaohs,”” connecting the Nile River to the Red Sea….

WIKI: Canal of the Pharaohs

At least as far back as Aristotle there have been suggestions that perhaps as early as the 12th Dynasty, Pharaoh Senusret III (1878–1839 BC), called Sesostris by the Greeks, may have started a canal joining the River Nile with the Red Sea. In his Meteorology, Aristotle wrote:

One of their kings tried to make a canal to it (for it would have been of no little advantage to them for the whole region to have become navigable; Sesostris is said to have been the first of the ancient kings to try), but he found that the sea was higher than the land. So he first, and Darius afterwards, stopped making the canal, lest the sea should mix with the river water and spoil it. [10]

Strabo also wrote that Sesostris started to build a canal, as did Pliny the Elder (see quote further down).[11]

However, the canal was probably first cut or at least begun by Necho II (r. 610–595 BC), in the late 7th century BC, and it was either re-dug or possibly completed by Darius the Great (r. 550–486 BC). Classical sources disagree as to when it was finally completed….

Canal of the Pharaohs: The Forerunner to The Suez Canal

…According to Greek historians Strabo and Diodorus Siculus, after Sesostris, work on the canal was continued by Necho II in the late 6th century BC, but he did not live to see the canal completed. Later, Darius the Great picked up from where Necho II left, but like Sesostris, he too stopped short of the Red Sea when he was informed that the Red Sea was at a higher level and would submerge the land if an opening was made. It was finally Ptolemy II who finished the canal connecting Nile with the Red Sea. According to Strabo the canal was nearly 50 meters wide and of sufficient depth to float large ships. It began at the village of Phacusa and traversed the Bitter Lakes, emptying into the Gulf or Arabia near the the city of Cleopatris…

So the idea of a canal linking the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea has been active since ancient times.

Wiki’s: Suez Canal give a history of the various attempts, successes, abandonment and retries over the centuries.

…It was re-excavated by Roman emperor Trajan in the first century AD… A geography treatise De Mensura Orbis Terrae written by the Irish monk Dicuil (born late 8th century) reports a conversation with another monk, Fidelis, who had sailed on the canal from the Nile to the Red Sea during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the first half of the 8th century… During the 16th century, the Ottoman’s made another try but it was too expensive… in late 1798, Napoleon expressed interest in finding the remnants of an ancient waterway passage…. Napoleon contemplated the construction of a north–south canal to connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. By avoiding the silt-laden Nile, such a canal would be easier to maintain. But the plan was abandoned because of the erroneous belief that the Red Sea was 8.5 m (28 ft) higher than the Mediterranean…. As late as 1861, the unnavigable ancient route discovered by Napoleon from Bubastis to the Red Sea still channelled water as far east as Kassassin…

At this point Wiki gets into the historic period of interest.

INTERIM PERIOD

Despite the construction challenges that could have been the result of the alleged difference in sea levels, the idea of finding a shorter route to the east remained alive. In 1830, General Francis Chesney submitted a report to the British government that stated that there was no difference in elevation and that the Suez Canal was feasible, but his report received no further attention. Lieutenant Waghorn established his “Overland Route”, which transported post and passengers to India via Egypt

The usefulness of this route for the British Empire was shown when dealing with the Indian Rebellion of 1857, with 5,000 British troops having passed through Egypt….

CONSTRUCTION

The British government had opposed the project from the outset to its completion. The British, who controlled both the Cape route and the Overland route to India and the Far East, favored the status quo, given that a canal might disrupt their commercial and maritime supremacy. 👉Lord Palmerston, the project’s most unwavering foe, confessed in the mid-1850s the real motive behind his opposition: that Britain’s commercial and maritime relations would be overthrown by the opening of a new route, open to all nations, and thus deprive his country of its present exclusive advantages.👈 As one of the diplomatic moves against the project when it nevertheless went ahead, it disapproved of the use of “forced labour” for construction of the canal. Involuntary labour on the project ceased, and the viceroy condemned the corvée, halting the project.

International opinion was initially skeptical, and shares of the Suez Canal Company did not sell well overseas. Britain, Austria, and Russia did not buy a significant number of shares. With assistance from the Cattaui banking family, and their relationship with James de Rothschild of the French House of Rothschild bonds and shares were successfully promoted in France and other parts of Europe….

The canal opened under French control in November 1869….

The canal had an immediate and dramatic effect on world trade. Combined with the American transcontinental railroad completed six months earlier, it allowed the world to be circled in record time. It played an important role in increasing European colonization of Africa.

The construction of the canal was one of the reasons for the Panic of 1873 in Great Britain, because goods from the Far East had, until then, been carried in sailing vessels around the Cape of Good Hope and stored in British warehouses.

An inability to pay his bank debts led Said Pasha’s successor, Isma’il Pasha, in 1875 [right after the end of the US Civil War when American Cotton became available again and depressed the price paid by Britian for cotton] to sell his 44% share in the canal for £4,000,000 ($19.2 million), equivalent to £432 million to £456 million ($540 million to $570 million) in 2019, to the government of the United Kingdom. [Actually the House of Rothschild] French shareholders still held the majority. Local unrest caused the British to invade in 1882 and take full control, although nominally Egypt remained part of the Ottoman Empire.

The British representative from 1883 to 1907 was Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, who reorganized and modernized the government and suppressed rebellions and corruption, thereby facilitating increased traffic on the canal….

At this point I am going to jump to a site in the UK.

The site is run by Stephen Luscombe a UK teacher who taught in France, the Middle East and Japan. He says:

First of all, I would like to make it clear that this site is not a rigorous academic site. I am sure there are plenty of mistakes and oversights on my part; for which I apologise in advance. My interest in the subject is purely that of a personal journey of discovery; to give myself a reason to research what I regard as a fascinating subject. Link

Egypt & The British Empire

rade links had existed between the two countries for as long as anyone could remember. Egypt was a key part of the old spice and trade routes between Europe and Asia. British traders had been loading and unloading their cargoes in Ottoman waters for generations.

British military and political interest in Egypt first manifested itself as it became obvious that in the Eighteenth Century, India was falling under the influence of Britain (and away from France). Despite, the direct sail routes around the Cape of Good Hope, Egypt still provided the quickest way of maintaining communications between Britain and and India. It required a brief overland journey, but it was still substantially quicker than circumnavigating Africa. India. It required a brief overland journey, but it was still substantially quicker than circumnavigating Africa….

He then goes into Napoleon attempted grab, the rise of the Egyptian leader, Muhammed Ali and the Brits & Ottomans defeat of this Egyptian leader. This is followed by the French involvement and the building of the canal.

…It was the French who were thought to be the most active in the North Africa region. They funded the Suez Canal and steadily increased their economic base in the country. British interest in Egypt developed during the American Civil War. At this time, British mills were starved of cotton. Alternative sources had to be found and one such source was to be Egypt whose cotton was actually a particularly good quality product. British companies began investing heavily in the production of cotton in Egypt. The hugely ambitious public works programs of the ruling Khedives also attracted British businessmen and their wares. Although, Egypt’s inability to pay for these modern conveniences was not yet thought to be a barrier to trade.

British strategic interest in Egypt was captured in 1869 when the Suez Canal was officially opened. The sailing times from London to Bombay were dramatically cut. British maps and ideas of the world had to be radically altered. The fact that the canal was controlled by the Khedive and the French government was initially a serious concern to the British. Although, It is from this point on that British decisiveness and speed of actions which consistently outwitted and out-manouevered the French and brought Egypt under Imperial British control. The first opportunity to pull away from the French was in 1875 when it became obvious that the Khedive had got himself into serious economic difficulties. The only way he could stave off creditors was by raising a seriously large amount of money. It was at this point that Disraeli was able to step in and offer to buy the Khedive’s shares in the Suez Canal Company. The speed of action on this event left the French reeling. Overnight, the British went from being a minority shareholder to being the controlling shareholder. Her influence had grown considerably as a result…

In only a few years the Egyptian government was again in economic difficulties. This time, the British and French governments initiated a stewardship of the finances of Egypt. In effect, this stewardship was little more than a joint form of colonization. British and French experts were to be sent to the various ministries in order to take control of day to day business of them. The Khedive’s unwillingness to agree to such loss of control was rewarded by his forced abdication and replacement by his son Tawfiq. The steady loss of sovereignty was keenly felt by many Egyptians. So much so that in 1882, Arabi Pasha initiated a revolt from inside the Egyptian army. In June of that year, riots broke out against the Europeans in Egypt. From this point on Britain took the initiative. The French refused participation in a bombardment of Alexandria due to political problems back at home. Surprisingly for a Liberal government, The British finally resolved on intervention and sent an expeditionary force to the Suez Canal. The Arabists were rapidly defeated at Tel el-Kabir in September and Cairo was occupied the next day. Accidentally, the British had found themselves to be masters of Egypt….

ative Council was suspended. After the Ottomans declared war on the allies on October 29th 1914, the British moved swiftly to break the technical link between the Ottoman Empire and the status of Egypt. The fate of the Suez Canal was just too important to take any chances and technically it was in enemy territory if Egypt was indeed a suzerain of Turkey. Indeed, Britain declared that the Canal was closed to all but allied and neutral shipping – despite international agreements to the contrary. Additionally, they deposed the Turcophile Khedive Abbas (who happened to be in Turkey at the time of their declaration of war) and created the new title of Sultan of Egypt on 19 December 1914 and engineered the pro-British Hussein Kamel to ascend the new position. The newly created Sultanate of Egypt was declared a British Protectorate rather than colony meaning that its people were subject of the Sultan rather than of King George. Hussein Kamel’s accession brought to an end the de jure Ottoman sovereignty over Egypt. But when Great Britain proclaimed this protectorate over Egypt in 1914, Saad Zaghlul’s benign attitude towards British rule changed fundamentally. The proclamation of the British protectorate united many of the different opposition groups in Egypt, and would become the starting point for Zaghlul’s new nationalism after the war.

The post-war international climate saw an increase in ideas of self-rule and independence – partly inspired by talk of Wilson’s 14 points, but also by a surge in national identities brought about by the war. Egypt’s nationalists, temporarily, saw how the rest of the Ottoman Empire was being divided up and wanted to be granted similar rights. Within days of the armistice Saad Zaghlul, the unofficial leader of Egyptian nationalism, headed to the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Reginald Wingate, and informed him that the Egyptian people wanted their complete independence and that he would like to lead his delegation to London to negotiate with the British government.

The British government initially refused mindful of the continued importance of Egypt as a strategic concern. They did relent to say that they would meet with the Egyptian Prime Minister, but sensing the change in nationalist sentiment in his country, he not only refused but resigned. Saad Zaghlul called for a nationwide revolt. However, as martial law had not yet been rescinded, the authorities used their extensive powers to arrest Saad Zaghlul and deport him to Malta. This further inflamed nationalist sentiment and escalated into the 1919 revolution.

Riots broke out and Lord Allenby and Milner [of the Miner Round Tables -GC] were despatched from Britain to try and ascertain what to do next. They quickly came to the conclusion that it was better to grant independence to pro-British Egyptians rather than wait for nationalists to take power for themselves. Saad Zaghlul was released and allowed to return from Malta much to the joy of many Egyptians. However, negotiations over granting independence whilst still maintaining British troops in key positions, especially with regards to the Suez Canal, dragged on for two more years. Saad Zaghlul was once more sent into exile to the Seychelles, yet in reality both Allenby and Milner were of a like mind and resented the fact that it was politicians back in London who were delaying the inevitable. Eventually, it was Allenby who threatened to resign if independence were not granted. Lloyd George finally capitulated and agreed…

1920-30s

the newly installed King Fuad resented the constitutional challenges from the Egyptian Parliament and oscillated between undermining its power and having to turn back to Parliament to raise money. This lack of political stability in Egypt undermined its own influence. However, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935 concentrated minds and a renewed negotiation with Britain finally bore fruit with a new Treaty in 1936.

The treaty, under which Britain still retained a prominent if diminished influence, was to run for 20 years; both parties were committed to negotiating a further alliance in 1956, at which point Egypt would have the right to submit to third-party judgement the question of whether British troops were any longer necessary in Egypt. The British occupation of Egypt was formally ended, though British troops were to remain in some areas. As Egypt’s self-defence capability improved, they would be withdrawn gradually to the Canal Zone and Sinai where their numbers would be limited to 10,000. And Britain reserved the right of reoccupation with the unrestricted use of Egyptian ports, airports and roads in war-time…..

Although this is a favorable view of the History of the British Empire as expected from a British school teacher, it is very helpful since he has a column on the right with a timeline and with links to other articles.

Unfortunately, my free time has been drastically shortened so I will leave it to people to delve into this history of Egypt as they wish. I will be looking at the more recent history next week since it is critical to understanding the Middle East of today.