What is it that feeds our battle, yet starves our victory?

Do We Still Need the Kang (Mis)Quote?

I’m still using the quote about winning the battles but losing the war. It seems like this doesn’t make sense right now given that we seem to be going from triumph to triumph.

On the contrary. This is the exception that proves the rule. The quote isn’t just a lament, it’s to point out why we can never seem to win.

You see, the RINOs cannot interfere and that is why, just for once, we are actually winning. And that is just one more piece of evidence (for the willfully blind) as to what I have been saying with that quote.

It stays.

Speaker Johnson

Pinging you on January 6 Tapes

Just a friendly reminder Speaker Johnson. You’re doing some good things–or at least trying in the case of the budget–but this is the most important thing out there still hanging. One initial block released with the promise of more…and?

We have American patriots being held without bail and without trial, and the tapes almost certainly contain exculpatory evidence. (And if they don’t, and we’re all just yelling in an echo chamber over here, we need to know that too. And there’s only one way to know.)

Either we have a weaponized, corrupt government or we have a lot of internet charlatans. Let’s expose whatever it is. (I’m betting it’s the corrupt weaponized government, but if I am wrong, I’d like to see proof.)

Justice Must Be Done.

The 2020 election must be acknowledged as fraudulent, and steps must be taken to prosecute the fraudsters and restore integrity to the system.

Yes this is still true in spite of 2024. Fraud must be rooted out of our system and that hasn’t changed just because the fraud wasn’t enough to stop Trump winning a second term. Fraud WILL be ramped up as soon as we stop paying attention.

Otherwise, everything ends again in 2028. Or perhaps earlier if Trump is saddled with a Left/RINO congress in 2026, via fraud.

Small Government?

Many times conservatives (real and fake) speak of “small government” being the goal.

This sounds good, and mostly is good, but it misses the essential point. The important thing here isn’t the size, but rather the purpose, of government. We could have a cheap, small tyranny. After all our government spends most of its revenue on payments to individuals and foreign aid, neither of which is part of the tyrannical apparatus trying to keep us locked down and censored. What parts of the government would be necessary for a tyranny? It’d be a lot smaller than what we have now. We could shrink the government and nevertheless find it more tyrannical than it is today.

No, what we want is a limited government, limited not in size, but rather in scope. Limited, that is, in what it’s allowed to do. Under current circumstances, such a government would also be much smaller, but that’s a side effect. If we were in a World War II sort of war, an existential fight against nasty dictatorships on the brink of world conquest, that would be very expensive and would require a gargantuan government, but that would be what the government should be doing. That would be a large, but still limited government, since it’d be working to protect our rights.

World War II would have been the wrong time to squawk about “small government,” but it wasn’t (and never is) a bad time to demand limited government. Today would be a better time to ask for a small government–at least the job it should be doing is small today–but it misses the essential point; we want government to not do certain things. Many of those things we don’t want it doing are expensive but many of them are quite eminently doable by a smaller government than the one we have today. Small, but still exceeding proper limits.

So be careful what you ask for. You might get it and find you asked for the wrong thing.

Political Science In Summation

It’s really just a matter of people who can’t be happy unless they control others…versus those who want to be left alone. The oldest conflict within mankind. Government is necessary, but government attracts the assholes (a highly technical term for the control freaks).

His Truth?

Again we saw an instance of “It might be true for Billy, but it’s not true for Bob” logic this week.

I hear this often, and it’s usually harmless. As when it’s describing differing circumstances, not different facts. “Housing is unaffordable” can be true for one person, but not for another who makes ten times as much.

But sometimes the speaker means it literally. Something like 2+2=4 is asserted to be true for Billy but not for Bob. (And when it’s literal, it’s usually Bob saying it.) And in that sense, it’s nonsense, dangerous nonsense. There is ONE reality, and it exists independent of our desires and our perceptions. It would go on existing if we weren’t here. We exist in it. It does not exist in our heads. It’s not a personal construct, and it isn’t a social construct. If there were no society, reality would continue to be what it is, it wouldn’t vanish…which it would have to do, if it were a social construct.

Now what can change from person to person is the perception of reality. We see that all the time. And people will, of course, act on those perceptions. They will vote for Trump (or try to) if their perception is close to mine, and vote against Trump (and certainly succeed at doing so) if their perception is distant from mine (and therefore, if I do say so, wrong). I have heard people say “perception is reality” and usually, that’s what they’re trying to say–your perception of reality is, as far as you know, an accurate representation of reality, or you’d change it.

But I really wish they’d say it differently. And sometimes, to get back to Billy and Bob, the person who says they have different truths is really saying they have different perceptions of reality–different worldviews. I can’t argue with the latter. But I sure wish they’d say it better. That way I’d know that someone who blabbers about two different truths is delusional and not worth my time, at least not until he passes kindergarten-level metaphysics on his umpteenth attempt.

Lawyer Appeasement Section

OK now for the fine print.

This is the Q Tree Daily Thread. You know the drill. There’s no Political correctness, but civility is a requirement. There are Important Guidelines, here, with an addendum on 20191110.

We have a new board – called The U Tree – where people can take each other to the woodshed without fear of censorship or moderation.

And remember Wheatie’s Rules:

1. No food fights

2. No running with scissors.

3. If you bring snacks, bring enough for everyone.

4. Zeroth rule of gun safety: Don’t let the government get your guns.

5. Rule one of gun safety: The gun is always loaded.

5a. If you actually want the gun to be loaded, like because you’re checking out a bump in the night, then it’s empty.

6. Rule two of gun safety: Never point the gun at anything you’re not willing to destroy.

7. Rule three: Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire.

8. Rule the fourth: Be sure of your target and what is behind it.

(Hmm a few extras seem to have crept in.)

(Paper) Spot Prices

Kitco “Ask” prices. Last week:

Gold $3,238.00

Silver $32.33

Platinum $954.00

Palladium $942.00

Rhodium $5,850.00

FRNSI* 155.638+

Gold:Silver 100.155-

This week, 3PM Mountain Time, markets have closed for the weekend.

Gold $3,329.00

Silver $32.65

Platinum $976.00

Palladium $984.00

Rhodium $5,750.00

FRNSI* 160.040+

Gold:Silver 101.960+

Gold went ballistic earlier this week and fell back a bit Thursday (markets closed Friday because it’s good, apparently). Up 91 bucks over the course of the week!

Silver continues to be lackluster. This 100+ to 1 ratio is ridiculous.

*The SteveInCO Federal Reserve Note Suckage Index (FRNSI) is a measure of how much the dollar has inflated. It’s the ratio of the current price of gold, to the number of dollars an ounce of fine gold made up when the dollar was defined as 25.8 grains of 0.900 gold. That worked out to an ounce being $20.67+71/387 of a cent. (Note gold wasn’t worth this much back then, thus much gold was $20.67 71/387ths. It’s a subtle distinction. One ounce of gold wasn’t worth $20.67 back then, it was $20.67.) Once this ratio is computed, 1 is subtracted from it so that the number is zero when the dollar is at its proper value, indicating zero suckage.

Apollo 13

This video is actually intended as an argument against those who think the moon landings were faked. However, it has a TON of information on the Apollo 13 mission, and a lot of the options NASA considered–it’s worth watching for all of that.

A Quick Guide to Wavelengths.

Optical astronomers think in wavelengths. Radio astronomers think in frequencies. (This is logical because circuits such as those used in receivers are designed in frequencies.) Sometimes it’s helpful to bridge that gap.

Approximating the speed of light as 300,000,000 meters per second (it’s actually 299,792,458 meters per second):

300 MHz is a one meter wavelength (and recall the FM band runs from 87-108 Mhz).

3 GHz (gigahertz=one billion cycles per second) is a ten centimeter wavelength (microwave ovens operate at 2.45 GHz).

30 GHz is a one centimeter wavelength.

300 GHz is a one millimeter wavelength.

Moving up to terahertz (trillion cycles per second)

300 THz is one micrometer wavelength. This is definitely an infrared frequency. (0.7 to 0.4 micrometers is visible light running from red to violet.)

A BIG Anniversary

I was halfway through writing about carbon dating but A) I could think of a joke to make about it for Pat F., but it wasn’t particularly racy, so she’d have been bored. B) This morning I realized what day this was. And that it’s the 250th anniversary of that date.

A quarter of a millennium.

If I can memorialize the 2500th anniversary of Thermopylae and Salamis, I can and absolutely should do THIS.

I have to apologize in advance; I had little time to do this and essentially just summarized what I was reading in Wikipedia. It might not “flow” well in many places.

Wikipedia dates the American Revolution as running from 1765 to 1783. Not 1775. And that’s because the Revolution began in the culture before it began on the battlefield.

Discontent began in 1763 shortly after France was defeated in the “French and Indian War” (which was a small piece of the Seven Years War, which, it could be argued was the actual first world war). American colonists had fought in the war, but that wasn’t good enough for the British Parliament, which imposed taxes to pay for the war. They also closed off the newly-won lands (in essence everything between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River) for settlement, turning over control of those lands to British officials in Montreal.

One of the most infamous of the taxes was the Stamp Tax, which passed in 1765. Printed matter (newspapers, magazines, legal documents, and even playing cards) had to produced on stamped paper produced in London, which included an embossed revenue stamp. So the tax itself was bad enough, but you had to donkey with importing paper from England. Oh, and the tax had to be paid in British currency, which was scarce in the colonies. (The idea was for money to flow from the colonies to Britain…not the other way around.)

The colonists hated this tax, and considered being taxed by a Parliament that they had no representation in to be a violation of their rights as Englishmen. The counterargument was that 90 percent of people living in Britain owned no property and thus had no vote, but were “virtually” represented by land owners who had common interests with them. This was a pretty stupid argument, because what does some guy in Virginia have in common with a land owner in England? One could argue that some unlanded Brit in Bumphucqueshire was represented in Parliament via a landowner in Bumphucqueshire but that works poorly for an American colonist who is 3000 miles away from the nearest land owner with a vote. Besides which even American landowners weren’t represented in Parliament.

There was enough upset over this that individual colonial legislatures (all except Georgia and North Carolina) passed resolutions, and then from October 7-25 of 1765, the Stamp Act Congress convened. Delegates from 9 of the colonies ( Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and South Carolina) attended. Why did the other four not attend? Virginia and Georgia’s assemblies were prevented from meeting by their governors (who, remember, were shills of the Crown). New Hampshire had some sort of financial crisis going on, and took no action, but after adjourning the legislature wanted to reconsider–the governor refused to call it back into session. North Carolina’s assembly had been prorogued by the lieutenant governor for other reasons. Nova Scotia (which included Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick) declined to send delegates. Quebec, Newfoundland, and East and West Florida did not have assemblies.

This congress produced the Declaration of Rights and Grievances. This document proclaimed loyalty to the crown, but insisted that only representatives chosen by the colonists could levy taxes. The document lauded the King; the complaints were about Parliament.

This was rejected by Parliament. However, the Stamp Act was repealed on March 18, 1766 due to pressure from within England. Merchants there were afraid of colonial boycotts. But note Parliament did not concede that they had no right to tax the colonies, and they would try again.

The Stamp Act Congress was the first significant organized political action of the American Revolution…though at that time, almost no one in the colonies was seeking independence.

Tensions flared again in 1767 with the passage of the Townshend Acts. This is actually an umbrella term for about five (historians differ on which ones should be included) acts: The Revenue Act of 1767 (the assholes were trying again), The Commissioners of Customs Act 1769, the Indemnity Act 1767, The New York Restraining Act 1767, and the Vice Admiralty Court Act 1768.

(The second to last might not be a bad idea today, at least as applied to their federal prosecutors.)

The idea was to raise revenue in America to pay judges and governors (all royal appointees), enforce trade regulations (which favored Britain), punish New York for not complying with the Quartering Act, and of course to ensure that there was precedent for Parliament to tax the colonies.

This was a HUGE shove towards the war. Colonists opposed to the acts gradually got violent, leading to the Boston Massacre (1770). American ports refused to import British goods. This was enough to get Parliament to repeal most of the taxes, with the prominent exception of the one on tea, retained mainly to demonstrate that Parliament was allowed to tax the colonies. Resenment continued, exacerbated by corrupt British officials. Colonials started attacking British ships, burning the Gaspee in 1772.

Parliament passed the Tea Act in 1773, granting the British East India Company a tea monopoly (and saving it from bankruptcy), which led to the Boston Tea Party that year.

Parliament passed the “Intolerable Acts” (the Brits called them the “Coercive Acts” which is at least an honest description) in 1774, in retaliation. These were five punitive laws. The first four targeted Massachusetts: Boston Port, Massachusetts Government, Impartial Administration of Justice [so much for honest descriptions], and Quartering Act. Massachusetts lost much of its self-government. The fifth act expanded Quebec further south into the Ohio country…which is now American territory.

Said Lord North (Prime Minister) on 22 April 1774:

The Americans have tarred and feathered your subjects, plundered your merchants, burnt your ships, denied all obedience to your laws and authority; yet so clement and so long forbearing has our conduct been that it is incumbent on us now to take a different course. Whatever may be the consequences, we must risk something; if we do not, all is over.

The fuckwit Lord North

Although the acts targeted Massachusetts, colonists in the other twelve colonies were outraged. Committees of correspondence formed in the Thirteen Colonies, the First Continental Congress met in September 1774 to coordinate a protest. And militias began drilling.

It was only a matter of time, now. Americans by and large were loyal to the Crown even at this time, their complaint was with Parliament. (Only sometime after shooting started did it become plain that the Crown was siding with Parliament–and that, combined with writing by Thomas Paine vastly better than this ramble you’re reading right now, is what shoved our founders over the edge.)

Fast forward to 1775, and once again Massachusetts is front and center. (They were as annoying to tyrants back then as they are to Patriots now.)

Massachusetts patriots had formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in opposition to the co-opted Massachusetts colonial government, and of course the militias were drilling. The Provincial Congress effectively controlled all of Massachusetts outside of Boston (which was effectively occupied by Britain).

In February 1775, the British Government declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. (Not quite, assholes…but you’d make it come true…)

700 British Army regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith were secretly ordered to capture and destroy Colonial military supplies stored in Concord by the militia. On the evening of April 18th the Colonials somehow found out that the seizure would happen the very next day: April 19th 1775, two hundred fifty years ago today. This was quite an intelligence coup; most of the British officers had not been told yet. There is speculation that General Gage’s wife (born in New Jersey) was the leaker.

Between 9 and 10 pm Joseph Warren (a friend of Margaret Gage) told Paul Revere and William Dawes that the Brits were embarking on boats from Boston to Cambridge, there to pick up the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren believed based on his sources (whoever they were) that the main objective was to arrest Adams and Hancock. They weren’t too worried about Concord; the supplies had long since been moved elsewhere. But they were concerned that the Colonial leaders in Lexington were unprepared. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn Lexington and the militia in nearby towns.

Revere gave instructions to send a signal to Charlestown using lanterns hung in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church. (Yes, you read that right. The lanterns were a signal from Paul Revere.) Revere then sailed north out of Boston, evading the HMS Somerset which was anchored nearby. (Crossings were banned at that hour.) He then rode on to Lexington, warning almost every house along the way.

In Lexington, Dawes, Revere, Adams and Hancock met with the militia and concluded that the force being sent was too big to be just for arresting Adams and Hancock; they concluded that Concord was the main target. Revere and Dawes continued on to Concord, accompanied by Samuel Prescott. They ran into a British patrol led by Major Mitchell at Lincoln; Revere was captured, Dawes was thrown from his horse. Prescott was the only one to reach Concord.

The warnings brought by Revere, Dawes, and Prescott triggered a system of “alarm and muster” that had been worked out in response to a prior seizure of powder from a militia near Boston. (These people knew not to give up their guns.) Dozens of eastern Massachusetts militias mustered in response to over 500 British regulars leaving Boston.

Those early warnings were the key to success.

The Brits disembarked near Phipps Farm in Cambridge, and began the 17 mile march to Concord at 2 am. They had had to wade ashore, so their uniforms and shoes were wet and muddy. They overheard the Colonial alarms and knew they had lost the element of surprise.

At 3 am Colonel Smith sent Major Pitcairn ahead with six companies of light infantry to quick march to Concord. En route an hour later Smith decided to send a message back to Boston to request reinforcements.

PItcairn’s advance guard entered Lexington at sunrise on April 19. About 80 Lexington militiamen under the command of Captain John Parker emerged from Buckman Tavern and stood in ranks on Lexington Common watching the Brits. This militia was not one of the “minuteman” companies, but rather a unit that trained other militias. There were also between 40 and 100 spectators along the side of the road.

Parker knew he was outmatched. He wasn’t about to sacrifice his men for no reason…and there was no reason. The supplies in Concord had already been removed to safety. There was no war, not yet (wait a few hours). Also the British had gone on such missions before and usually found nothing and simply went back to Boston. Parker figured that would happen this time; the Brits would go back to Boston, with nothing to show about it other than a day’s exercise.

Parker put his men into parade ground formation. They were in plain sight, not blocking the Brits. He is recorded as ordering, “Stand your ground; don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” His deposition from shortly after the battle:

I … ordered our Militia to meet on the Common in said Lexington to consult what to do, and concluded not to be discovered, nor meddle or make with said Regular Troops (if they should approach) unless they should insult or molest us; and, upon their sudden Approach, I immediately ordered our Militia to disperse, and not to fire:—Immediately said Troops made their appearance and rushed furiously, fired upon, and killed eight of our Party without receiving any Provocation therefor from us.

Captain John Parker of the Lexington Militia

But I get ahead of myself.

The Brits arrived, and an officer (probably Pitcairn) rode forward, ordering the militia to disperse. He may have also ordered them to lay down their arms. Parker ordered his men to disperse. Unfortunately his voice was injured by tuberculosis, and few heard him. Those that did, dispersed slowly taking their guns with them.

Both sides ordered their men to hold their fire…but someone fired a shot.

We’ll never know who.

Some claimed one of the onlookers fired the shot from concealment (if not cover). Some said it was a mounted British officer. There’s general agreement that the shots did not come from the front lines.

We like to call it a battle, but objectively it was a skirmish. That states its scale accurately, but hugely understates its importance.

The British had no trouble gaining control in Lexington, after some chaos.

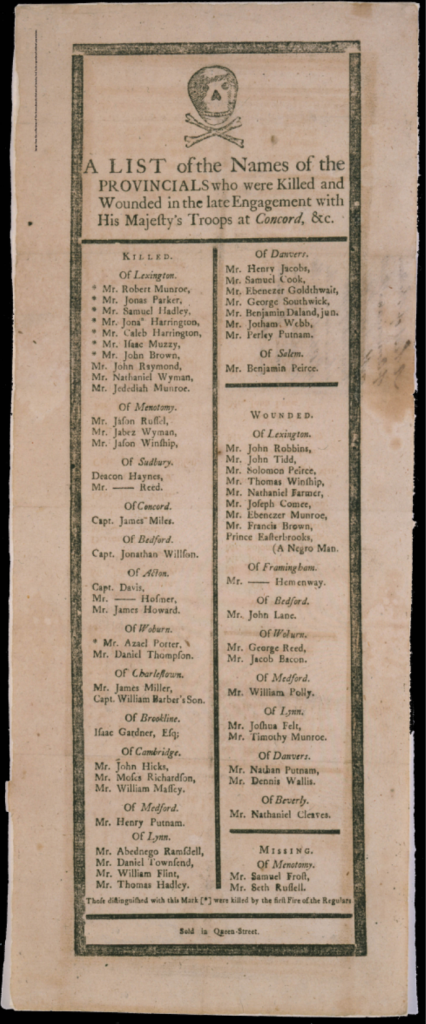

Let us note the names of the eight Lexington men who perished in this skirmish. These were the first eight Americans to die in the American Revolutionary War.

John Brown, Samuel Hadley, Caleb Harrington, Jonathon Harrington, Robert Munroe, Isaac Muzzey, Asahel Porter, and Jonas Parker.

Jonathon Harrington, fatally wounded by a British musket ball, managed to crawl back to his home, and died on his own doorstep. Jonas Parker (cousin to John Parker) was run through by bayonet. One wounded man, Prince Estabrook, was a black slave who was serving in the militia.

There was one British casualty, shot in the thigh.

The Brits got out of control largely because they didn’t know what they were supposed to be doing there. Colonel Smith, when he arrived, had a drummer beat assembly, ending the fiasco. The light infantry were permitted to fire a victory volley, then the column reformed and marched on towards Concord.

The Concord militia (and militias from neighboring villages) was unsure what to do; a column of 250 militia marched out to meet the Brits on their way, but seeing they were outnumbered, turned around and went back. The militia then assembled on a hill about a mile north of the North Bridge.

The British arrived, and divided; some went to secure South Bridge, 100 or so to secure North Bridge. Another group went two miles further than the North Bridge to Barrett’s Farm, which was believed to be one of the places supplies had been cached. Some more regulars guarded the return route. Captain Walter Laurie, in charge of the North Bridge and Barret forces was uncomfortably aware that he was outnumbered by the Colonials and requested reinforcements.

The grenadiers searched the town of Concord. Some of them focused on Ephraim Jones’s tavern, because they had intel that cannon were buried there. Jones at first wouldn’t let them in, but at gunpoint revealed where three 24 lb cannon were located. (These were yuuuge cannon, better at battering fortifications than for defense.) The trunnions of the cannons were smashed, making it impossible to mount them. Some gun carriages were found at the village meetinghouse and burned. Provisions and 550 pounds of musket balls were thrown into a millpond.

Then the Brits left. In fact they had been scrupulous in their treatment of the people; they even paid for food and drink they consumed. The locals took advantage of this, giving bad directions and saving several smaller caches of supplies.

Nothing was found at the Barrett farm. (That doesn’t mean there wasn’t anything there; far from it.)

The Brits stationed at the North Bridge retreated and the colonials under the command of Barret (as in “farm”) advanced toward the bridge, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. British captain Laurie ordered a retreat across the bridge, and then he made a mistake. He ordered his men to form positions for “street firing” in a column perpendicular to the river. This was a weird call (this formation was appropriate for firing down a street, but this was a rural setting) and there was a lot of confusion.

Then a shot rang out, likely a panic shot from a tired British soldier.

Two more Brits fired into the river, and others, thinking they had been ordered to fire, did so in a volley.

Two minutemen from Acton were hit and killed instantly. Let us note their names: Private Abner Hosmer and Captain Isaac Davis.

Major Buttrick then ordered the militia to return fire. At this point the opposing lines were 50 yards apart. The first volley by the Militia killed three British privates, injured eight officers and sergeants and nine privates.

The regulars, outnumbered, poorly led, and quite possibly having no experience in combat, retreated in panic, abandoning their fallen. They met the grenadiers coming from town toward the North bridge to reinforce them (in response to Laurie’s request).

The Brits at Barret’s Farm were cut off. When they later marched back to Concord, they walked right through the battlefield, seeing dead and wounded comrades.

The Brits in Concord finished their search, ate lunch, and left Concord after noon, heading for Boston. This allowed more militia to arrive from outlying towns, lining the road to Boston.

Initially, Lieutenant Colonel Smith sent flankers to follow a ridge and protect his forces.

(Side note: The common mental image of the British mindlessly marching in formation doing nothing at all to counter pot shots from the Americans is a false one; it was the job of flankers to move along the flanks and take on anyone inclined to do this.)

Unfortunately for the Brits that ridge ended about a mile east of Concord at Meriam’s Corner, where there was a bridge across Elm Brook. The British had to pull the flankers back into the main column and march three abreast to cross that bridge. The militia leaders could see this would have to happen and they converged on that bridge.

Nevertheless the Brits crossed the bridge unmolested except by intermittent distant and ineffective fire. However the British rear guard turned about and fired a volley at the militia which had closed towithin musket range. The colonists returned fire, killing two and wounding six Brits and taking no casualties. The British flankers were sent out again after crossing the bridge.

Another mile to Brooks hill, where 500 militiamen had assembled on the south side of the road waiting to fire down upon the Brits. Smith’s leading forces charged the hill to drive them away, but the colonists stood their ground and inflicted significant casualties.

Another bridge into Lincoln, and more militia. And then things got worse. The road rose and curved sharply left through a wooded area. The Woburn militia had positioned themselves to the southeast of the bend in a rocky lightly wooded area. More militia, coming in from Meriam’s Corner, set up on the other side of the bend, and the Brits got caught in a crossfire. More militia were coming up on the column from behind. Five hundred yards after this, the road bent sharply to the right and the Brits got caught in another crossfire. Casualties in this double-bend were about 30 (killed and wounded combined) for the Brits, and four militia killed, among them Captain Jonathan Wilson of Bedford, Captain Nathan Wyman of Billerica, Lt. John Bacon of Natick, and Daniel Thompson of Woburn.

The British soldiers escaped by breaking into a trot, a pace that the colonials (who weren’t on a road) could not match through the woods and swamps. Unfortunately the militia on the road in pursuit were too densely packed and disorganized to do much more than harass the Brits.

Anyhow, you can see how this is going, and I’m running short on time. The Brits used their flankers where possible oftentimes getting behind the militias and inflicting casualties, but this was the death of a thousand cuts for the Brits.

Nearing Lexington, the Lexington militia–that had lost eight people earlier in the day–laid an ambush. Lt. Colonel Smith was wounded in the thigh and knocked from his horse. Pitcairn assumed command and sent light infantry to clear the militia forces.

They weren’t even halfway back. So here I really must cut it short and leap to the end–except to note that the worst was yet to come for the Brits: Menotony and Cambridge. And as the day wore on they became more and more likely to commit atrocities in spite of the best efforts of their officers.

The Brits made it back to Boston. Colonials: 49 killed, 39 wounded, 5 missing. Brits: 73 killed, 174 wounded, 53 missing. Considering this was militia against regulars…that’s a much more lopsided loss than it looked. It’s primarily the result of the Brits suddenly finding themselves deep inside enemy territory; territory of the enemies they had spent the last ten years making.

The next morning Boston was surrounded by fifteen thousand militia, and it was a war now. Boston was under siege. The forces surrounding it grew over the next few days.

Those forces would soon become the Continental Army, by resolution of the Second Continental Congress, on June 14th.

Militarily this wasn’t a huge battle, but strategically it was a huge faceplant for the British. The point of the Intolerable Acts was to prevent fighting, the expedition was supposed to prevent fighting as well, and instead it had touched off a war.

Now there was a war for British political opinion. The Provincial Congress collected scores of sworn testimonies from militiamen and British prisoners. A week after the battle, word got to the Colonials that Gage was sending his official description of events to London; the Provincial Congress sent a packet of over 100 depositions to London by a faster ship. They ended up printed in London newspapers two weeks before Gage’s report arrived. It turned out his report was vague. Even George Germain (no friend of the colonists) stated that the Bostonians were in the right. Gage was made a scapegoat, when the real problem was British policy. The British troops in Boston blamed either Gage or Colonel Smith.

The day after the battle, John Adams rode along the battlefields and declared that the Rubicon had been crossed. Thomas Paine had up to then considered the argument “a kind of law-suit” but now he “rejected the hardened, sullen-tempered Pharoah of England forever.” (And remember this was the man whose essay did more than anything else to convince Americans that they should pursue independence, not reconciliation.)

On hearing the news, George Washington at Mount Vernon said:

the once-happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched in blood or inhabited by slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice?

Two hundred and fifty years later, we know the choice that was made. And we know that we made it stick.

And we must never forget that this work is never done.