The Great Conjunction

Instead of politics, I’m going to talk about what’s about to happen on the 21st at about 5PM.

Jupiter and Saturn, which appear in the southwestern sky shortly after sunset, will appear in our sky only 6 arc minutes apart. When they come close to each other like this, it’s called a Great Conjunction, because it’s the rarest of all possible conjunctions involving planets visible with the naked eye.

The central black hole of the Milky Way Galaxy is somewhere in that direction also. (Photo by me.)

That is one fifth of the apparent width of the full moon.

It’s also about the width of six quarters, laid out side to side, at a hundred yards, or about a six inch wide object at that distance.

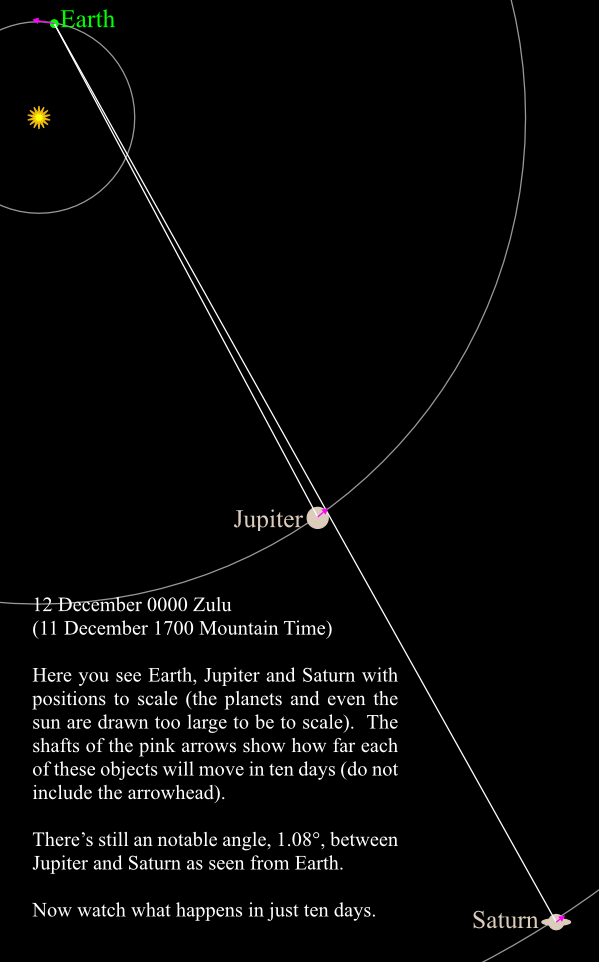

As of 5 PM Friday the 11th, Mountain Time, or 0000 Zulu on the 12th, they are 1.08 degrees apart in the sky, which is to say about 65 arc minutes. (60 arc minutes makes a degree).

I know this because I downloaded a bunch of sun-centered coordinates for Earth, Jupiter and Saturn from the NASA website, built a spreadsheet to do the calculations to center the coordinates on earth, then did a vector cross product of the normalized vectors and took the arcsine. (That either meant something to you…or it didn’t!) What you are about to see here in my diagrams, below, is the real stuff, with the real planetary positions, as best as I can draw it; it’s not some notional cartoon.

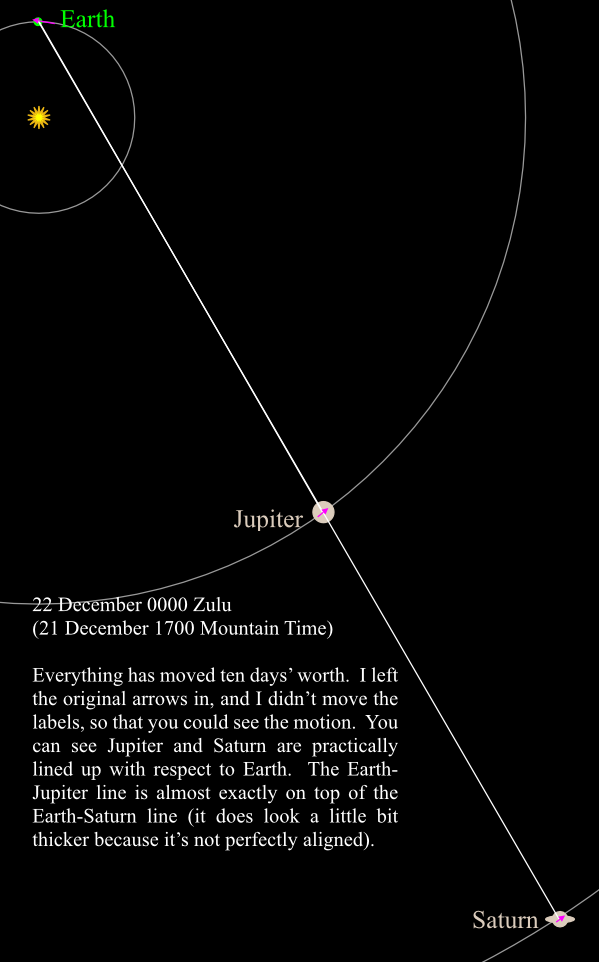

As of 5 PM on the 21st, Mountain Time, the separation is 0.105 degrees, which is 6.3 arc minutes.

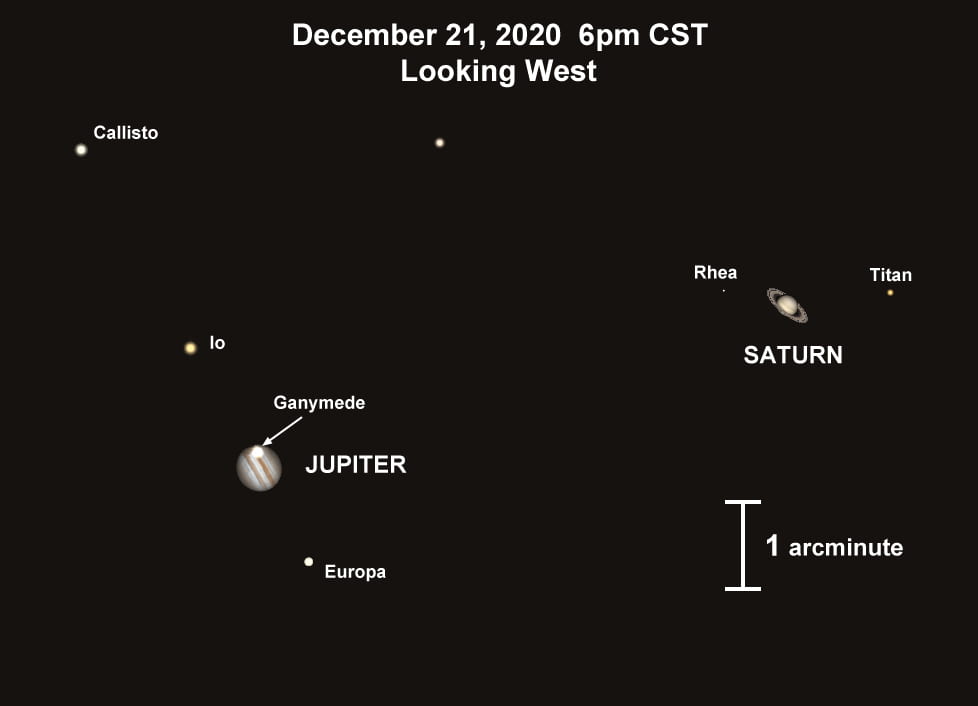

If you look through a telescope at 5PM MST on the 21st, this is what you will see:

Yes, you will see Jupiter and Saturn in the SAME field of view, without having to shift!

Now if you’ve been watching Jupiter and Saturn since this summer, when they were essentially right on top of the Summer Milky Way Galaxy, you noticed they were close. They don’t seem much closer today, but they’re going to get a lot closer, a lot faster now.

What’s going on?

Again, going back to my NASA data dump, I can create a picture, looking down from above the Sun’s north pole, of 5 PM on the 12th. The dots representing the planets and sun are actually much too large, but the distances are to scale.

(One thing I had to cheat on is the orbits, I drew them as perfect circles centered on the Sun,

and they really aren’t, quite, but they’re close.)

The arrows correspond to how fast (and in what direction) the planets are moving around the Sun, and they’re even scaled…the length of the shaft of the arrow is how much it will move in ten days (ignore the head of the arrow, which is sized to be bigger than the shaft for Saturn’s arrow).

Earth is “up” from the Sun in this diagram because the way the coordinate system is defined, it’s on the X axis to the right of the sun at the beginning of fall (in the northern hemisphere). A quarter of a year later, Earth has moved almost ninety degrees around its orbit, so it will be near the Y axis, “above” the Sun.

You can see that the earth is moving one way (“left” on the diagram), and Jupiter and Saturn are moving the other way (right-ish), and furthermore that Jupiter is catching up to Saturn. (Since both Jupiter and Saturn are moving in nearly-circular orbits, and Jupiter is closer to the Sun, Jupiter moves faster than Saturn, and Earth moves faster still. See Kepler’s second and third laws.) With Jupiter to the left of the Earth-Saturn line, and moving rightwards towards that line, and Earth moving to the left, dragging one end of the Earth-Saturn line with it, Jupiter’s going to find itself on that line pretty doggone quickly.

(One thing I had to cheat on is the orbits, I drew them as perfect circles centered on the Sun,

and they really aren’t, quite, but they’re close.)

Shazam, you now have the closest conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter (by definition as seen from Earth) in about 800 years!

But you might think, doesn’t this happen every time Jupiter “laps” Saturn? Jupiter, moving around the Sun once every 12 years, will lap Saturn, moving around the sun every 28 years, every 20 years or so. And indeed there is a great conjunction just about every 20 years, sometimes even multiples in that year if the timing is such that Earth zig-zags across the Saturn-Jupiter line.

But most great conjunctions aren’t really this close as seen from Earth. The reason that’s not plain here is that these pictures do not, and cannot, tell the whole story. They’re two dimensional and the full story is three dimensional.

Although the orbits almost lie in the same plane, they do not. And that difference is critical. The diagrams are set up so that they show the Earth’s orbital plane, also called the plane of the ecliptic. Jupiter’s is tilted by 1.31 degrees, and Saturn’s is tilted 2.48 degrees. So it turns out that right now, those planets would, in fact, be slightly inside your screen if it were a 3D display. If you take the Earth’s orbit’s radius (not diameter) as “1 Astronomical Unit” then Jupiter is almost exactly 5% or 1/20th of that distance inside your screen. Saturn is 7% of that distance into your screen. You can hopefully imagine the line from Earth descending at a shallow gradient into the screen, going through Jupiter, then continuing its descent and almost crossing through Saturn, which is just a bit deeper into the screen.

Different great conjunctions occur when Jupiter and Saturn are at different spots in their orbits, and in many cases one of them will be above the plane of your computer screen while the other one is below it. What you’d see here on Earth when that happens is one of them crossing considerably to the north of the other in the sky, rather than almost–almost–right on top of each other.

That’s why this great conjunction is so special. They’re not just lined up on my diagram (as they would be every 20 years or so), they’re damn close to being lined up in three dimensions, so from Earth, you will see Jupiter almost directly in front of Saturn, and that is rare! (Though it will happen again in sixty years–today’s young adults and children will have another shot at this–but after that, wait four centuries or so.)

It’s important to note that the planets never actually get close to each other. Jupiter and Saturn are further apart than the distance from the Earth to the Sun. It’s just that sometimes they are almost on the same line of sight as seen from here.

Star of Bethlehem?

This event is being hyped as the “Star of Bethlehem.” But whatever it was that happened then, it probably wasn’t a great conjunction. Trying to nail down just what the original Star of Bethlehem actually was (assuming it isn’t completely mythical) has been an occasional pastime for nearly two thousand years. We don’t know the year, and frankly, we don’t even know the season. (There’s no actual scriptural warrant for the nativity being in late December.) The nativity is described in two of the gospels, Matthew and Luke, with the Star of Bethlehem only appearing in Matthew’s account. The time indications in the two gospels are actually years apart (Herod’s reign ended in 4 BC, Quirinius didn’t become governor of Syria until 6 AD). Even if there’s a way to reconcile that through some new historical discovery, which year would the reconciliation point to?

People seeking an astronomical event that could have been the Star of Bethlehem therefore have to search over at least a ten year range. Well there was a Great Conjunction in 7 BC (in fact they got three of them because the Earth managed to zigzag across the Jupiter-Saturn line that year), but it wasn’t close enough to be very impressive, and 7 BC was almost certainly too early anyway.

But there was a very close conjunction of Jupiter and Venus in 2 BC, near Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, on June 17. It was certainly more visually striking, because Venus is far brighter than Saturn, and the conjunction was closer than any of the three great conjunctions in 7 BC, to boot. This could be a candidate.

2002 Triple Conjunction

There was a series of conjunctions, albeit not involving Jupiter, in 2002. I remember there was quite a clustering of planets in the evening sky that year. According to Wikipedia:

Venus, Mars and Saturn appeared close together in the evening sky in early May 2002, with a conjunction of Mars and Saturn occurring on 4 May. This was followed by a conjunction of Venus and Saturn on 7 May, and another of Venus and Mars on 10 May when their angular separation was only 18 arcminutes. A series of conjunctions between the Moon and, in order, Saturn, Mars and Venus took place on 14 May, although it was not possible to observe all these in darkness from any single location on the Earth.

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjunction_(astronomy)

Note that Venus and Mars got to within three times the distance Jupiter and Saturn will get on the 21st. If you happen to remember that, this is going to kick its ass.

Conjunctions Involving The Sun

Oftentimes a planet will have a conjunction with the Sun, and when that happens they will generally just say, for example, “Jupiter is in conjunction” without naming the Sun. It’s assumed.

The Sun will be passing in front of Jupiter and Saturn in a couple of months, as seen from Earth; just imagine in my diagrams Earth moving further around its orbit quite quickly while Jupiter and Saturn move much more slowly, and you’ll “see” it happening.

There won’t be much to see, of course, because to see the event, you have to do so when the Sun is above the horizon, and that, of course, is daytime.

Since Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are further out from the Sun than Earth is, when we see a conjunction involving those planets and the sun, the planet is always “behind” the sun.

But what about Mercury and Venus? They can have conjunctions where they are on the other side of the sun, or conjunctions where they are between us and the sun. The former are called superior conjunctions and the latter, inferior conjunctions.

Again, because their orbits are tilted with respect to ours, they don’t pass directly behind (or in front of) the Sun that often, usually looking like they are to the south or north of the Sun at closest approach.

But every once in a while one of these planets will pass in front of the sun (which is a big broad target compared to any other planet), and that’s called a transit. Venus in particular generally has pairs of conjunctions 8 years apart…but the pairs are separated by about a century. When this happens you can, with glasses of the type you’d use to look at the sun near an eclipse, actually see a little black dot on the face of the sun, even without a telescope. This last happened in 2004 and 2012, so if you missed it you are SOL, the next occurrence is in December 2117. (And yes, I was watching in 2012.)

Venus transits are of huge historical importance; they gave us our first good way of measuring the size of Earth’s orbit and (since we already knew the proportions) hence the size of just about everything in the Solar System. (Or, equivalently: It told us how big an “astronomical unit” was in more earthly measurements; since we already knew the size of everything in the Solar System in AUs, we could now give distances in furlongs, if we wanted to, by multiplying.)

Here’s a deep dive on Venus transits (including why they are important) that I wrote at the time, and a later article including pictures I took.

Raw data

This is the position and velocity data I pulled off the NASA website. Sun is at (0, 0, 0). Distances are in AU (astronomical units), velocity is in AU/day. 1 AU by definition is 149,597,870,700 meters (92,955,807 miles, 1441 feet, 6.898- inches), it was originally defined as the semi-major axis of the Earth’s orbit, and a day is precisely 86,400 seconds (no matter how much the Earth slows down rotating). The diagrams were created at the scale of 100 pixels = 1AU, and they appear to have come across (into WordPress’s editor at least) at the proper size.

EARTH:

2459195.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-12 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X = 1.622579957389862E-01 Y = 9.761221058229992E-01 Z = 5.373489375534890E-05

VX=-1.724242466206539E-02 VY= 2.883832025215380E-03 VZ= 6.987175827141265E-07

2459205.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-22 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X =-1.188898588832658E-02 Y = 9.897218187033275E-01 Z = 6.029984014237024E-05

VX= 6.031051355304800E-03 VY= 4.767506691437359E-03 VZ=-1.546747270590170E-04

JUPITER:

2459195.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-12 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X = 2.914228592894236E+00 Y =-4.177510430316559E+00 Z =-4.786920225992232E-02

VX= 6.095603857740477E-03 VY= 4.674926465555783E-03 VZ=-1.557747700228924E-04

2459205.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-22 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X = 2.974861050901444E+00 Y =-4.130298866311659E+00 Z =-4.942153470106487E-02

VX= 6.031051355304800E-03 VY= 4.767506691437359E-03 VZ=-1.546747270590170E-04

SATURN:

2459195.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-12 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X = 5.396386096136037E+00 Y =-8.396666010466467E+00 Z =-6.884059973895380E-02

VX= 4.382900563538985E-03 VY= 3.001959812133514E-03 VZ=-2.266077336665883E-04

459205.500000000 = A.D. 2020-Dec-22 00:00:00.0000 TDB

X = 5.440127588899244E+00 Y =-8.366514834723951E+00 Z =-7.110831635421563E-02

VX= 4.365303571900237E-03 VY= 3.027110022628067E-03 VZ=-2.263327688903255E-04A Reminder Of Today’s Big Issue.

Our movement is about replacing a failed and corrupt political establishment with a new government controlled by you, the American People...Our campaign represents a true existential threat, like they’ve never seen before.

Then-Candidate Donald J. Trump

Needs to happen, soon.

Lawyer Appeasement Section

OK now for the fine print.

Please note that our menu has changed, please listen to all of the options.

This is the WQTH Daily Thread. You know the drill. There’s no Political correctness, but civility is a requirement. There are Important Guidelines, here, with an addendum on 20191110.

We have a new board – called The U Tree – where people can take each other to the woodshed without fear of censorship or moderation.

And remember Wheatie’s Rules:

1. No food fights

2. No running with scissors.

3. If you bring snacks, bring enough for everyone.

4. The first rule of gun safety: Don’t let the government take your guns.

5. The gun is always loaded.

5a. If you actually want the gun to be loaded, like because you’re checking out a bump in the night, then it’s empty.

6. Never point the gun at anything you’re not willing to destroy.

7. Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire.

8. Be sure of your target and what is behind it.

9. Social Justice Warriors, ANTIFA pukes, BLM hypocrites, and other assorted varieties of Marxists can go copulate with themselves, or if insufficiently limber, may substitute a rusty wire brush suitable for cleaning the bore of a twelve or ten gauge.

(Hmm a few extras seem to have crept in.)

Coin of The Day

No coin today.

But I told Grandma In TX that’s she’d hit a 1000 today [Friday], and that triggered someone to talk about a grand grandma, and I remembered something.

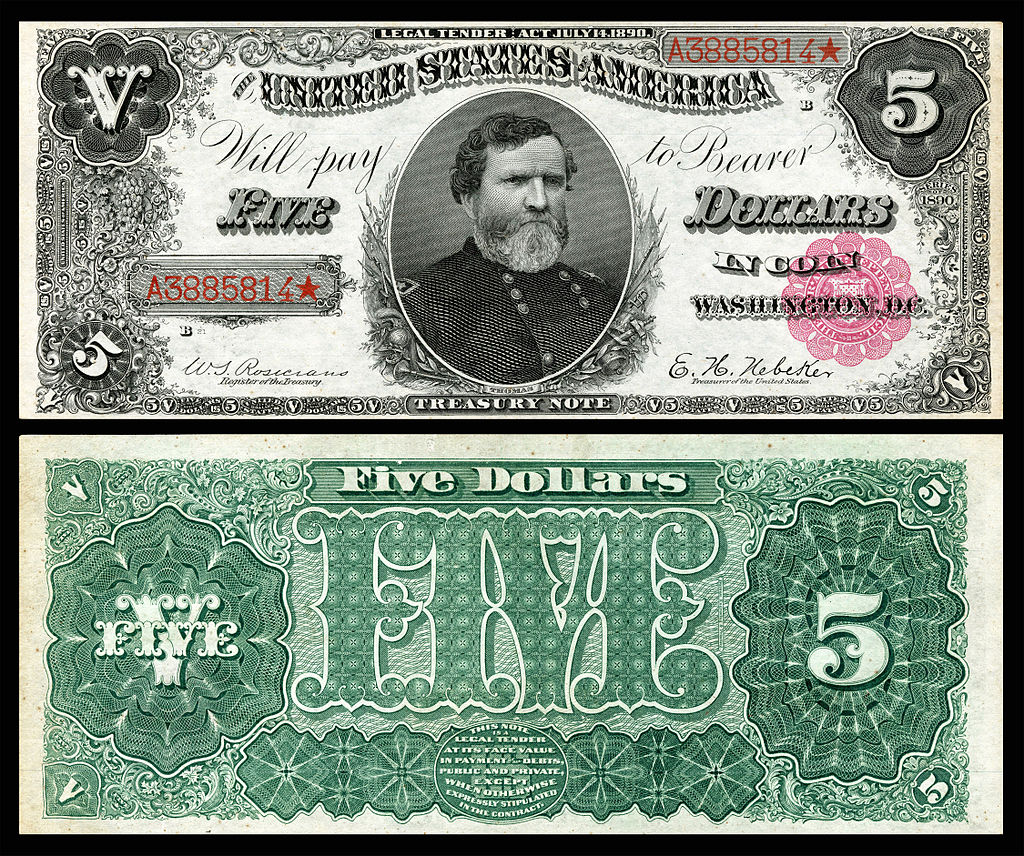

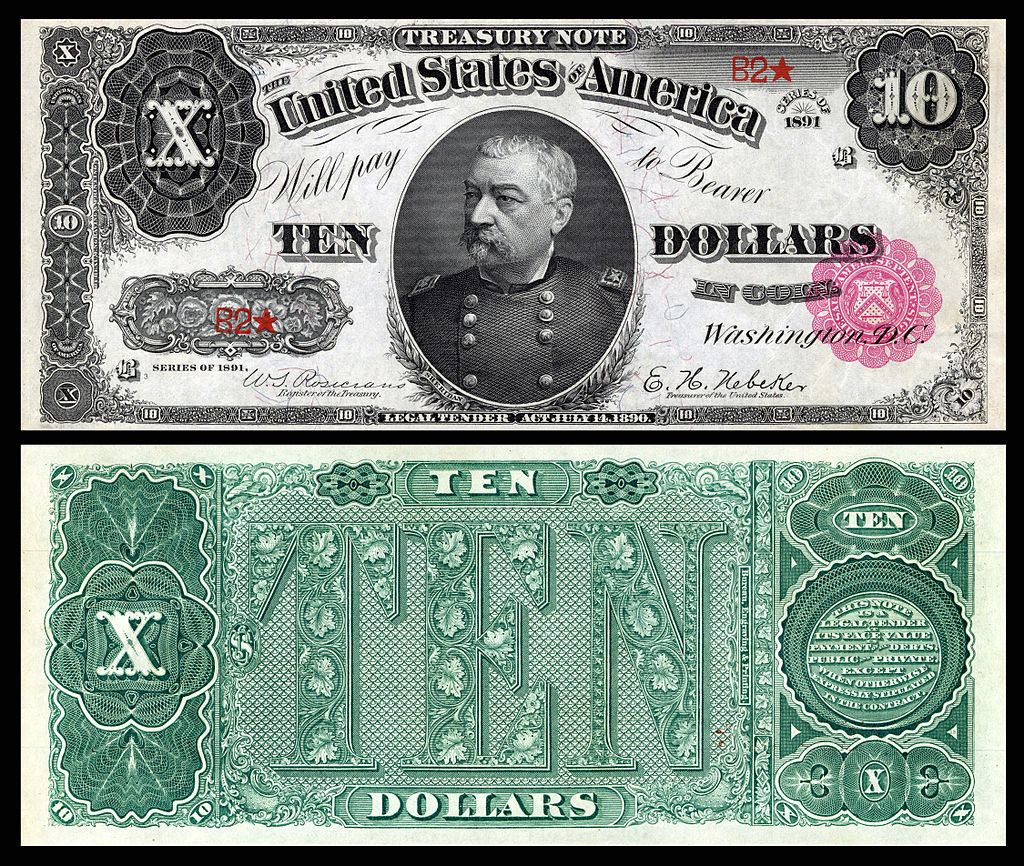

In 1890, the US issued “Treasury Notes” or “Coin Notes” in many denominations. This and 1891 were the only years they issued paper money of this specific category, The specific use was to pay for purchasing silver bullion (which, of course, would then be made into coins). You could redeem these notes, just like silver or gold certificates, but the government could decide whether it’d be in silver or gold coin. Every denomination available today was covered, $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, and there were also $500 and $1000 notes.

The ones issued in 1890 look very different from the 1891 notes, and are called “patternback” notes, for reasons you’ll soon understand. The $50 and $500 were not issued in 1890, so the patternback notes only exist for $1-$20, $100, and $1000 denominations.

This series features a lot of Civil War flag officers on it, many of them obscure to people who are not active Civil War buffs.

Portrait is of Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War (i.e., the Army) during the Civil War.

Note there is a very elaborate repeating pattern inside the denomination on the reverse; that’s why it’s called a patternback. (In heraldry, sometimes there’s an elaborate repeating background pattern in a coat of arms…it’s actually, I am not making this up, called “diaper” but presumably not in front of the knight whose coat of arms it was.)

Moving along, here’s the $2, $5, $10, and $20

Now there is a thing to know about these old “large size” (the size of one of those old computer cards) notes. They get extremely rare in some cases. Notes tended to wear out quickly and rapidly get redeemed, even if only for a newer note. If someone actually set aside twenty dollars back then, trying to save the note…well, they had more money than they knew what to do with; remember that was very close to being a full ounce of gold!

That $20 in VF-20 (the number is on a scale of 1-70) will set you back at least six thousand dollars, and that’s actually relatively affordable for an old $20. A silver certificate from 1878 or 1880 is simply impossible in such a grade (my book doesn’t list anything higher than F-12), later series get down to about the same range as this patternback.

The true nosebleed territory starts with the $50 denomination. There are literally notes where there are no known survivors. Others are marked “Extremely Rare” and “One known” and the book doesn’t even try to give a price. But as there isn’t a patternback $50, we’ll move on to the stratosphere now.

Portrait is of Admiral David Farragut

The “big” denomination on this wasn’t spelled out like the others, and the pattern ended up resembling a watermelon on the two zeros, so this is known today as the watermelon note. And it will cost you a hundred…thousand…dollars in VF-20. The good news is, in EF-40 it “only” goes up to $170,000 instead of doubling or tripling like I’d usually expect. The book gives no price for higher grades.

Now I can at least see spending 6 or 8 grand on a collectible note…but a hundred thousand dollars? Thank you but no, I’d rather have a house!

Now on to the last note.

We skip over $500, since there was no patternback $500. (By the way, before we stopped printing $500 as federal reserve notes, they had McKinley on them. McKinley comes after Franklin. (And if you want to know: Grover Cleveland on the $1000, James Madison on the $5000, Salmon Chase on the $10,000 and Woodrow-be-damned Wilson on the $100,000.)

Portrait is of General George Meade

The One Thousand Dollar Patternback keeps the “melon” look of the C-note, and is called the Grand Watermelon.

My book calls these “extremely rare.” One in AU (about uncirculated, the numerical grade would be in the 50s) is the very first US note to sell for over a million dollars. There’s another variant with a small red seal overprint on the front, instead of the big brown one you see here; two are known to exist.

When a note is this rare, you don’t care about the fact that someone scribbled their name and a date (presumably 1893) on it!

So in honor of the Grand Grandma, here’s a Grand Watermelon.

And it’s 9:58 Mountain Time. Just barely made the deadline!!!

Standard disclaimer: I never show pictures of my own coins. I may or may not own coins like the ones I show. Burglars will be interested to hear that gold and silver aren’t the only heavy metals I have, and I have quite a bit of one with a heavier nucleus than either. And I keep it around a lot more than the gold and silver.

And a note to the other authors. Wikipedia URLs do paste into posts (select media style of paragraph via the plus sign, and use the option to paste in a URL). That’s how I did this Grand Watermelon picture–I noticed the option only after I had uploaded all of the pictures, having downloaded them from Wikipoo, and decided to give the alternate route a try with the Grand Watermelon. (I guess I wasted Wolf’s space.)

Obligatory PSAs and Reminders

Just two more things, my standard Public Service Announcements. We don’t want to forget them!!!

How Not To Find Yourself In Contention For The Darwin Award

(Nothing to do with bearded dragons)

It has been pointed out that all of the rioting is nominally on account of criminals who resisted arrest in one form or another, and someone suggested schools ought to teach people not to resist arrest.

Chris Rock on a similar vein, in 2007

Granted an “ass kicking” isn’t the same as being shot, but both can result from the same stupid act. You may ultimately beat the rap, but you aren’t going to avoid the ride.

China is Lower than Whale Shit

Remember Hong Kong!!! And remember the tens of millions who died under the “Great Helmsman” Chairman Mao.

中国是个混蛋 !!!

Zhōngguò shì gè hùndàn !!!

China is asshoe !!!

For my money the Great Helmsman is Hikaru Sulu (even if the actor is a dingbat).