Justice Must Be Done.

The prior election must be acknowledged as fraudulent, and steps must be taken to prosecute the fraudsters and restore integrity to the system.

Nothing else matters at this point. Talking about trying again in 2022 or 2024 is hopeless otherwise. Which is not to say one must never talk about this, but rather that one must account for this in ones planning; if fixing the fraud is not part of the plan, you have no plan.

The Audit

The Audit is definitely heating up. Let’s see if the Opposition manages to squelch it and its consequences. I’ll be honest; I expect it to be ignored by anyone capable of ordering Biden/Harris to step down.

Nevertheless, anything that can be done to make Biden look less legitimate is a worthy thing!

Lawyer Appeasement Section

OK now for the fine print.

This is the WQTH Daily Thread. You know the drill. There’s no Poltical correctness, but civility is a requirement. There are Important Guidelines, here, with an addendum on 20191110.

We have a new board – called The U Tree – where people can take each other to the woodshed without fear of censorship or moderation.

And remember Wheatie’s Rules:

1. No food fights

2. No running with scissors.

3. If you bring snacks, bring enough for everyone.

4. Zeroth rule of gun safety: Don’t let the government get your guns.

5. Rule one of gun safety: The gun is always loaded.

5a. If you actually want the gun to be loaded, like because you’re checking out a bump in the night, then it’s empty.

6. Rule two of gun safety: Never point the gun at anything you’re not willing to destroy.

7. Rule three: Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire.

8. Rule the fourth: Be sure of your target and what is behind it.

(Hmm a few extras seem to have crept in.)

Spot (i.e., paper) Prices

Last week:

Gold $1815.20

Silver $25.56

Platinum $1053.00

Palladium $2747.00

Rhodium $19,500.00

This week, 3PM Mountain Time, markets have closed for the weekend.

Gold $1763.90

Silver $24.48

Platinum $985.00

Palladium $2712.00

Rhodium $21,150.00

Gold was up in the 1810s all week up to Friday morning, but tanked HARD on that day, down $41.20. Everything took a beating, honestly, except rhodium which went up.

Part XIII – Rutherford On A Roll

We left off, circa 1903, having discovered radioactivity and the electron, and making quite a bit of progress with them.

To try to recap (and there are a few things in this so-called “recap” that I should have mentioned earlier, but didn’t), an electron is a negatively charged particle about 1/1830th the mass of a hydrogen atom, which up to then had been the lightest thing known to exist. They could be knocked off of atoms in a Crookes tube and they would then form what was called a cathode ray (yes, the same “cathode ray” in those big tubes in those old boxy TVs). It is possible to strip one electron off a hydrogen atom, at which point the remaining piece of the hydrogen atom (called an ion) had a positive charge that balanced the electron’s negative charge. The atom as a whole was neutral, charge 0; the individual pieces also added up to 0. Even though there was plenty of mass left in the ion, easily enough for hundreds more electrons, no one could get a second electron to come out of a hydrogen atom.

Thomson, the discoverer of the electron, suggested that atoms were fairly solid spheres of positive electrical charge with little electron inclusions that could be knocked out to ionize the atom; this was called the plum pudding model of the atom.

Radioactivity had been discovered in 1896. Uranium and thorium, it turns out, are radioactive. Radioactivity turned out to consist of three types of rays, alpha, beta, and gamma.

Alpha rays turned out to be identical to doubly-ionized helium, i.e., helium from which two electrons had been stripped (and there was no sign of being able to strip away a third electron from helium). Helium itself had been discovered on Earth back in 1895, trapped in a uranium ore; its atomic mass was four times that of hydrogen. Clearly the helium had begun as alpha particles, then combined with electrons in the ore to become helium gas. The charge of an alpha particle is 2e.

Beta rays turned out to be high-speed electrons. Their charge, of course, is –e.

Gamma rays turned out to be electromagnetic radiation, extremely strong electromagnetic radiation, like X-rays on steroids. Gamma rays, like all photons, have no electrical charge at all.

Alpha rays could be stopped by a sheet of paper. Beta rays could penetrate many sheets of paper, but would be stopped by a thin sheet of metal. Gamma rays required a lot of shielding to stop.

Uranium (atomic weight ~238) and thorium (atomic weight ~232), which had just been discovered to be radioactive, were the heaviest known elements, roughly 238 and 232 times as massive, atom for atom, as hydrogen. The Curies discovered that uranium ore was four times as radioactive as the ores it contained; they were able to isolate two new elements, radium (atomic weight 226) and polonium (atomic weight 210), by processing tons of the ore pitchblende.

It was also clear that a pure block of refined uranium would grow more radioactive over time, eventually reaching a level significantly higher than before, but not nearly as high as the ores.

In radioactive decay, the total amount of energy released, relative to the mass, turned out to be staggeringly huge, thousands if not millions of times more than what was released by burning chemicals. In 1904 Ernest Rutherford (who had named the three types of radiation, and who is the star of today’s story) suggested that radioactivity could provide enough energy to power the sun for the many millions of years necessary for Darwinian evolution to take place. (Previously known sources of energy were woefully inadequate; it was one of the 1895 mysteries I listed.)

At the time atomic weight was considered to be a defining characteristic of an element. This would cause some confusion for a few years.

Some stuff I should have covered previously, but didn’t:

The electric charge of an electron is about -1.602 x 10-19 coulombs. This is a negative number (because Benjamin Franklin arbitrarily picked one kind of charge to be positive and the other negative, and when the electron was discovered, it happened to be the one he tagged as negative), so, perhaps a bit counterintuitively, physicists define the minimum charge e to be +1.602 x 10-19 coulombs, i.e., -1 times the charge of an electron. Physicists, in fact, find it far more convenient to use e as the unit of electric charge when talking about atoms, that way they don’t have to sling 10-19s everywhere.

And they do something similar for energy. Just like a falling weight generates kinetic energy (a mass being attracted to another mass by gravity, speeds up that mass), an electron responding to one volt of electrical potential generates a certain amount of energy, which is defined to be an “electron volt.” This is abbreviated eV (which spell checkers will try to “fix” the capitalization of). This ends up being 1.602 x 10-19 joules. (Notice it’s the same factor, 1.602 x 10-19. This is a consequence of the way the joule, coulomb, and volt are defined.) Energy at the atomic level, particularly when dealing with chemical energy, tends to be a convenient, human-relatable number of electron volts.

And a reminder: An atomic mass unit was defined, in 1898, as 1/16th the mass of an oxygen molecule. This was very close to the mass of a hydrogen atom, but because oxygen reacted with more things, it was easier to use it as a yardstick. [This definition has since been modified, for reasons I’ll explain below.] It was equal to 1.6604675209 x 10-27 kilograms. (This is slightly different from today’s value.) It was abbreviated “amu.” Atomic weights were expressed in amu’s, so oxygen’s atomic weight was 16.0000, and hydrogen’s was almost exactly 1.0: In 1949, under this definition, it was measured at 1.008 amu. (At least, according to a 1951-52 CRC handbook–well, it’s a book that fits King Kong’s hand–that I happen to own.)

OK, so that, I believe, catches us up.

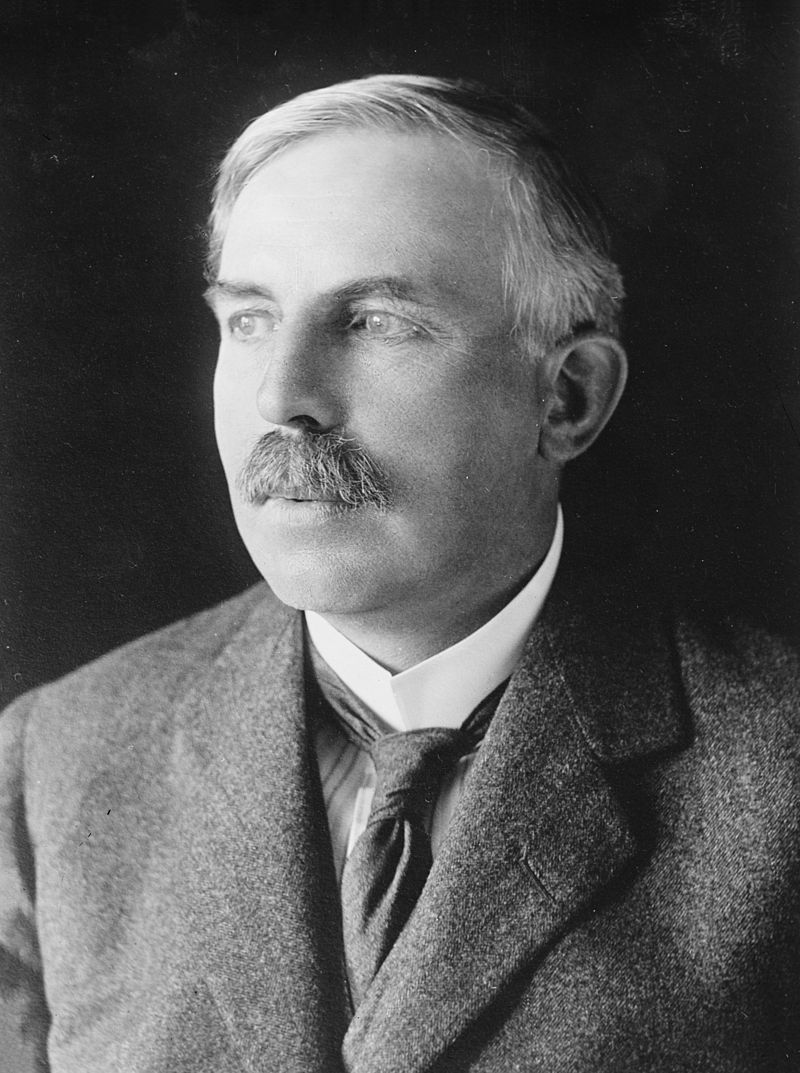

I’ll be honest, as I was researching this, I was surprised how many times Rutherford’s name kept coming up. I had known about a few of the things he had done (the gold foil experiment being the most famous) but in fact he was all over everything that happened, it seems. It seems he was at least in the room for a lot of things I talked about last time (like the discovery of the elctron).

He fully deserved having an element named after him (Z=104).

If parts of this caption make no sense…read on.

A Plethora of Radioactive Elements?

Scientists continued to investigate radioactivity. They would find more and more elements, distinguished by their atomic masses, in both uranium and thorium ores.

Even as early as 1900-1903 Rutherford was involved in this effort. Looking at thorium “emanations” with his student Frederick Soddy, they discovered thorium x and a gas, thoron. At first they thought these were special forms of thorium, but then they realized these were not thorium. By 1903 they had concluded that these emanations were the result of thorium changing into another element. This was a very bold conclusion, since chemists up to now had believed elements were immutable, that such things were alchemist balogna. (And under normal circumstances this was true…but radioactivity was something fundamentally new, and certainly nothing like what the alchemists had thought of.)

So perhaps these new elements could fill in the large gap between bismuth and thorium in the periodic table? Well, they could, but it turned out that in fact, there were way too many of them. Realistically between lead and uranium there was room for nine elements, and we already had five of them: bismuth, polonium, radium, radon (which was basically the thoron gas) and thorium. But just in uranium ore there seemed to be about thirty of them (based on my count looking at a chart in Wikipoo–perhaps they had found fewer than that before they figured out what was actually going on). Thorium ores brought in another ten or so.

But it was very, very difficult to separate out these putative elements. For instance Soddy in 1910 showed that mesothorium, atomic weight 228, radium, atomic weight 226, and thorium X, atomic weight 224, were impossible to separate chemically, as if they were the same element. But how could that be so when the atomic weights were different? Trying to place these elements in the table led Soddy and Kazimierz Fajans to independently come up with the notion of radioactive displacement in 1913. Basically, this stated that an alpha decay reduced an atom’s mass by about four amu (the mass of the alpha particle), and also moved it two places to the left on the periodic table. (If such a thing were to happen to (say) nickel, it would become iron, which is two spots to the left of nickel. But it won’t.) A beta decay left the mass almost unchanged (the mass of the electron that gets kicked out is relatively insignificant), but moved the element one place to the right. (If an atom of palladium were to undergo a beta decay, it would become silver. This has happened under very special circumstances, ones that won’t affect the palladium bullion I hope you own.) Gamma decay had no such effect; apparently it was just a way to get rid of energy.

For this work Rutherford won the 1908 Nobel Prize for Physics.

But he hadn’t even got started yet.

The Isotope

Now if one used the radioactive displacement principle, it appeared that two or more different “elements” could occupy the same place on the periodic table. The three I named above all fit in the same square, directly under barium. Because they occupied the same place, they were termed isotopes, from Greek for “the same place.”

So you had “elements” of different mass that otherwise behaved identically. At this point chemists decided that the mass wasn’t as important as the behavior, and swallowed the concept of two different atomic weights representing the same element, rather than insisting they must be different elements solely because of different atomic weights. Atomic weight wasn’t necessarily a crucial characteristic of an element, particularly when it came to ones extracted from radioactive ones.

In 1912, meanwhile, J. J. Thomson, who had discovered the electron in 1897 (with some help from Rutherford, it turns out) wasn’t done yet, had ionized neon (which was the tenth element listed on the periodic table at the time) in a Crookes tube and magnetically and electrically deflected its ions, the same way that he had deflected electrons in 1897, to determine the ions’ charge to mass ratio. He was quite surprised to see these ions, which should have weighed in at about 21.18 amus, went to two different locations! Some were deflecting more than others, because they were lighter than those others.

Assuming that they were singly ionized, with one electron removed (it takes a lot more energy to take the second electron off than it did the first), one group of ions had an atomic weight of almost exactly 20, the other had an atomic weight of almost exactly 22. The atomic weight of neon had been measured as 20.179, which made it one of those cases where the atomic weight was not almost a whole number, but now it looked like that was actually an average value. Most neon had atomic weight of almost exactly 20, but some came in at about 22, and the weighted (ahem) average was 20.179.

So now, even perfectly ordinary stable elements had isotopes, and this time no one thought these must be two different elements because the weights are different. In modern terms neon consists of a mix of neon-20 and neon-22.

I have mentioned in the past that many elements had “atomic weights” or “atomic masses” that were almost a perfect multiple of hydrogen’s. These mostly turn out to be elements with exactly one isotope in nature, or perhaps more than one isotope but one of them is much, much more common than the other(s).

Hydrogen, it turns out, has two isotopes found in nature, hydrogen-1 and hydrogen-2. Hydrogen-1 is overwhelmingly common, hydrogen-2 is rare, a bit more than one atom in ten thousand hydrogen atoms is hydrogen-2.

For various reasons, the isotopes of hydrogen actually ended up with “real” names–not true for any other element! Hydrogen-1 is called protium and hydrogen-2 is called deuterium.

The actual atomic mass of hydrogen is a bit higher than the atomic weight of pure protium expressed in kilograms, because the tiny amount of deuterium pulls the average up.

If, in an alternate universe, the atomic mass unit had been defined differently so that hydrogen–mixed hydrogen–got an atomic mass of 1 unit, this would actually have been slightly higher than the atomic mass of pure protium, because the occasional deuterium atom pulls the average up.

But in the real world, the atomic mass unit was defined to be 1/16th the atomic weight of oxygen. So oxygen was 16.0000 by definition. Hydrogen ended up being a hair more than 1.008. Could the excess be due to the deuterium? Not so fast. Oxygen, it turned out in 1919, consists of three isotopes. Oxygen-16 is overwhelmingly more common than oxygen-17 and oxygen-18. But even if you set pure oxygen-16’s atomic weight to 16.00 by definition, and then look at the atomic weight of pure protium, pure protium doesn’t come in at precisely 1.000. There’s still this slight tendency to be off just a bit from integers. At the time no one knew why, but they knew about it well enough to talk about a mass defect. But at least now, we understood the elements that were way off from being whole integer atomic weights–they were mixtures of isotopes. So this is a partial answer to one of our mysteries.

Physicists often discussed different isotopes of the same element. Chemists rarely did back then. Physicists used the whole number to label them, rather than the exact number. This whole number was termed the “mass number” and had the symbol A (from German Atomgewicht). I’ve been using these mass numbers a lot so far, and will continue to do so.

So we have three things with similar-sounding names. There’s the atomic mass unit (amu), almost (but not quite) equal to the mass of a hydrogen atom. There’s an atomic weight, measured in atomic mass units, which represents the mass of the atom. But there is also a mass number, which is a rounded version of the atomic weight, for a specific isotope. Hydrogen’s atomic weight is 1.0008, but the mass number of its most common isotope was just simply 1. When doing ordinary chemistry weighing out reactants the atomic weight is used to compute the number of moles of each reactant. When talking about isotopes, the mass number is used, without fail.

(Looking ahead a little: In the 1920s physicists began using a physical atomic mass unit, that really was based on oxygen-16 rather than mixed oxygen. To distinguish it from the other one, the prior one was called the chemical atomic mass unit–which the chemists kept on using. And then it turned out that oxygen obtained from water had a slightly different isotope mixture and hence real atomic weight, than oxygen extracted from the air. So the chemists’ unit was based on a foundation of quicksand. But even using the physical amu, the atomic weight of a pure isotope was still never a clean, perfect integer, except for oxygen-16.

(But now we had two slightly different units with very similar names. In 1961 they compromised, and created the “unified atomic mass unit” (symbol u, also called the dalton, symbol Da) that was 1/12th of the mass of a carbon-12 atom. This was closer to the chemists’ standard than to the physicists’.

(No matter what standard was chosen, however, the only isotope that had a perfect integer mass was the reference isotope. All others were off, just a bit.

(But that was all in the future. Let’s return to our story, back to 1912.)

The Nucleus

Backing up just a couple of years from there, there had been another very important discovery in 1909 by Ernest Rutherford. He was collaborating with Hans Geiger (who is definitely a counter) and Ernest Marsden.

They used a beam of alpha rays (which, as a reminder, are heavy and positively charged) to bombard a very thin layer of gold foil. They were pretty much expecting those alpha particles to plow through the “plum pudding” atoms. Instead, though most indeed cruised right through the gold atoms as if nothing were there, a very few of them bounced away at sharp angles, repelled by an intense and concentrated positive charge. Some even bounced back towards the beam source! Rutherford said, in a very famous quote: “It was quite the most incredible event that has ever happened to me in my life. It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

In 1911 Rutherford argued that those alpha particles were bouncing off an atomic nucleus. This meant that an atom consisted almost entirely of empty space. All of that positive charge (and almost all of the mass of the atom) was in a tiny, tiny, very dense body about 1/10,000th the width of the atom; the rest of the space was the domain of the electrons, which orbited the nucleus much like planets orbit the sun, except in this case the attractive force wasn’t gravity, but the attraction between the positively charged nucleus and the negatively charged electrons. This was a new model of the atom, called the “Rutherford Model.” Rutherford is credited with discovering the atomic nucleus.

And in fact that number understates things; according to modern measurements entire atoms can be anywhere from 26,000 to 60,000 times as wide as their nuclei. Which works to to be anywhere from 17.6 – 216 trillion times the volume.

Atomic Number

Later that year, Antonius van den Broek proposed that the sequential location of each element in the periodic table was equal to its nuclear charge, this charge (in units of e) was the atom’s atomic number. This fit well for hydrogen, which could only have one electron stripped off, leaving a +1e charged nucleus behind. And for helium, which could be ionized twice leaving a +2e charged nucleus behind. They were the first and second elements listed in the table. However, we couldn’t strip every atom down to a bare nucleus to see its charge; the heavier the atom the harder it was to do that.

This was a new concept. Chemists had talked about the atomic weight of an atom, never its number. You could list the elements in the order they appeared in the periodic table, of course (accounting for the very few unfilled “holes” in the grid), but the place on the list wasn’t considered terribly significant. But now it appeared as if charges came in discrete quantities, and given that one could only remove one electron from a hydrogen atom, and two from the atom with the next higher weight, the implication was that this nucleus had a specific charge, an integer multiple of the charge of an electron (but with the opposite sign). So hydrogen’s atomic number was 1, helium’s was 2. Lithium’s was 3. And so on, through carbon (6), oxygen (8), aluminum (13), iron (26), zinc (30), rhodium (45), silver (47), tin (50), platinum (78), gold (79), lead (82), thorium (90), and uranium (92), to give some examples. (However the exact numbers for anything above the upper fifties really weren’t certain at this point.)

This was only a suggestion…until about two years later. I will pick that story up next time, because it actually ties in more with electrons, and this week I want to concentrate on the nucleus. Suffice it for now to say that van den Broek was absolutely right. I’m going to reference the concept of atomic number, abbreviated Z (from German Zahl, ‘number’), from here forward.

The Proton

So, let’s continue Rutherford’s story. In 1917 he ran some more experiments. He fired alpha beams into air (which is mostly nitrogen), and detected hydrogen ions. After refining his experiment, he realized that the alpha particles were reacting with the nitrogen. When he reported his results in 1919, he claimed that the alpha particle had simply knocked a hydrogen nucleus out of a nitrogen nucleus, reducing the nitrogen nucleus’ charge (and atomic number) and weight by one and thereby turning it into carbon. Nitrogen-14 was seemingly becoming carbon-13, a rare (but stable) isotope of carbon, which is mostly carbon-12.

But by then we had cloud chambers and could see some forms of radioactivity and ions leaving trails through the chamber. In 1925, Rutherford examined some cloud chamber tracks of this reaction, and he realized he was totally wrong about what was happening. The alpha particle wasn’t bouncing off the nitrogen nucleus after knocking one proton out of it. No, it was disappearing. What was in fact happening was the nitrogen nucleus, 7 positive charges, total mass 14, was absorbing the alpha particle.

I mentioned, up above, the principle of radioactive displacement. An atom, spitting out an alpha particle moves two places to the left on the periodic table. That means its atomic number decreases by two. The atomic mass drops by four.

Absorbing an alpha particle has exactly the opposite effect. The atomic number increases by two, and the atomic mass increases by four. So the nitrogen-14 was becoming fluorine-18.

Immediately upon becoming fluorine-18, the nucleus then shed a proton, which was the hydrogen ion that Rutherford saw. This turned it into oxygen-17, stable but uncommon (most oxygen being oxygen-16).

But in the meantime, people had decided that that hydrogen nucleus was a basic particle, and it was named the proton. It’s regarded as having been discovered in 1919, since that was the first time it was seen to exist having come from some source other than hydrogen gas. or in 1920 when someone suggested it might be an elementary particle. Rutherford, as the discoverer, got to name it.

William Prout, clear back in 1815, had suggested that the other elements might be built up, somehow, from hydrogen, and now it looked like he was at least partly right. Hydrogen indeed consisted of a single proton, mass 1, and an electron, and other elements apparently had 2, 3, 4 or more protons, all the way up to uranium with 92 of them–each with a matching electron. You couldn’t just bundle hydrogen atoms together to get other kinds of atoms, but conceivably, if you separated the electrons and protons, then combined the protons, and put the electrons back in place, you could get larger atoms.

In fact, Rutherford had suggested both the name “proton” and the name “prouton” for this particle, the latter to honor Prout. (The English would have pronounced “prouton” as if it rhymed with “grout on”, and the French would have made it rhyme with “crouton” so we dodged a bullet of linguistic confusion there.)

The proton’s mass is 1.007 amus (using the modern AMU scale). Again, maddeningly close to a whole number. But because of this, the proton looked like the underpinning for atomic number but it couldn’t be the underpinning of atomic mass. That’s because, to take an example, oxygen’s nucleus has eight protons in it, but a mass of sixteen, twice as much as the protons. Uranium is even more out of whack. It has 92 protons, but its most common isotope has a mass of 238, leaving 146 mass units unaccounted for! Why? We didn’t know, yet.

In 1920, Rutherford voiced a suggestion. He thought that the excess mass consisted of a number of protons and electron pairs, bound to each other to make a net neutral bundle. So an oxygen-16 nucleus actually contained sixteen protons, but eight of them were bundled with, and masked by, electrons. The net positive charge is eight, and that’s critical because it requires eight orbiting electrons to balance out, and those eight orbiting electrons are responsible for oxygen’s chemical properties. So the chemical nature of an atom ultimately depended on the number of protons not in these bundles.

This actually made quite a bit of sense. Remember beta decay? This is where a nucleus can spit out an electron. The electron has a single negative charge. In order to make up for that loss, the nucleus has to gain a positive charge; it’s as if a new proton were appearing. But if Rutherford’s idea were correct, rather than a proton and an electron being magically created, one of these bound pairs was breaking apart, freeing the electron and unmasking the hidden proton.

Another thing arguing in Rutherford’s favor was the fact that whatever-it-is that was left over in the nucleus had a mass that was nearly that of a whole number of protons; it would make sense for the missing ingredient to be that number of “masked” protons.

Physicists would spend the 1920s thinking that the nucleus consisted of a number of protons equal to the mass number A, plus a bunch of nuclear electrons, which left a net number of “unmasked” protons equal to Z. With some mysterious “mass defect” making the total mass slightly off.

But there were some theoretical difficulties with this…which I will take up in a future installment.

Who Cares About Isotopes?

Until late in the last century, chemists almost never concerned themselves with differing isotopes. That’s because oxygen-16’s chemical behavior is nearly indistinguishable from oxygen-17’s. Because the oxygen-17 is a bit heavier, it’s perhaps a tiny bit slower to react than oxygen-16, but not much. If you were to liquefy oxygen-16 and oxygen-17, then measure their boiling points, the oxygen-17 would require a slightly higher temperature to boil, because it would take just a little bit more energy to kick those heavier oxygen-17 atoms into vapor. Melting and boiling points are in fact the biggest difference a chemist might see…if he had separated samples to work with in the first place. And chemical means of separation were simply untenable; they were too much alike.

Water made with oxygen-17 and oxygen-18 evaporates a bit less readily than water with oxygen-16, so rainwater tends to be slightly richer in oxygen-16 than seawater (and this is part of the reason we had to stop defining the atomic mass unit as 1/16th of mixed oxygen–the mix could differ depending on where you got the oxygen from).

The chemical differences between protium (hydrogen-1) and deuterium (hydrogen-2) are actually significant, due to the fact that proportionally, the difference is greater than for any other pair of isotopes. Water made out of deuterium (“heavy water”) instead of protium actually melts at 4C, rather than 0C. I’ve seen a video of a heavy water ice cube sunk to the bottom of a glass of cold (regular) water. It’s not going to melt as long as that water is properly chilled. Note that I said the bottom of a glass of cold water. It doesn’t float because it’s heavier than regular ice and heavier even than regular water. (Now, if it were in a glass of heavy water, it would float.)

And of course, heavy water, because of its significantly different chemical behavior, is toxic when pure.

Other than that, for “traditional” chemistry, isotopes just didn’t matter.

Today things are a bit different. Mass spectrometers–which are the descendant of Crookes tubes, designed to ionize, accelerate, and deflect atoms and molecules to see how much they deflect and thus figure out the masses–are relatively cheap, and they can read out absolute numbers of “hits” at each possible mass. So one can run a sample of water through one of these and get a very precise notion of the isotopic composition. Now, you can tell whether a sample of water was rain water or ground water. Or you can analyze a sample of metal and be able to tell where it was mined, because it turns out each mine has a slightly different isotopic mix of the metal. Or one can prove that CO2 was added to champagne artificially, because the CO2 used has no carbon-14 in it (whereas the carbon dioxide in fermentation does).

Incidentally, if you’ve ever had TSA swab your luggage then stuff the swab into a machine which tells them you aren’t carrying explosives–that device is a mass spectrometer.

That’s today. But back in 1910, chemists didn’t give a rip about isotopes. Physicists studying radioactivity, on the other hand, knew that “which isotope is this?” could make all the difference in the world. And that’s even more true today too, now that we can artificially make all sorts of radioactive isotopes that don’t exist in nature. We now have to concern ourselves with radioactive hydrogen-3 (“tritium”), cesium-137, iodine-131 and strontium-90…and these were elements that were never radioactive in the days of the Model T and the Wright Flyer.

In 1910 we were just starting down this road. Remember, Rutherford had made fluorine-18 and oxygen-17 artificially.

Decay Chains

Keep this in mind as we go back now to uranium (atomic number Z=92) and thorium (Z=90). Remember that whole process of figuring out the pieces of an atom started in part because of the discovery of radioactivity, a property of these two elements in particular.

At the time of today’s story, had become quite clear that when there was radioactivity, one kind of atom was changing into another, this is called “decay.”

Uranium and thorium decay very slowly, or I should say, uranium-235, uranium-238, and thorium-232 decay very slowly (as I said, the isotope matters). It’s a statistical process. When you are looking at one uranium-235 atom, it could decay a second from now…or it could wait a billion years. There’s no way to know when it will happen, but it’s almost a stable nucleus; it’s very, very unlikely to blow in the next second. And if that atom is still around in a billion years, someone watching it then is just as unlikely to see it go kablooey in the next second as you are today.

I’m going to get on a soap box here, for just a minute. Let’s say you watch someone flip a coin 20 times and it comes up tails each time. Do you think, “wow, it’s overdue to come up heads, I’ll bet it comes up heads next time?” If so, you have a “naive” view of probability. The more sophisticated view is that, since the tosses are independent events they aren’t affected by each other. The chance is 50/50 of heads next time, no matter how many times in a row it has come up tails just now. But then, there is the cynic’s view. He doesn’t believe the odds are fifty/fifty either. But he doesn’t figure it’s overdue to come up heads; he figures the coin probably is crooked; perhaps tails on both sides! And he might have a point there. The smart bet, if you’re not allowed to examine the coin, is probably to bet on “tails.” But, if the coin really is fair, the 50/50 view is correct.

Similarly, for the chances of an unstable nucleus going kablooey in the next second, or minute. A billion years from now, provided your unstable nucleus hasn’t gone kablooey in the meantime and it’s still around, it’s just as likely to not go kablooey in the next second, as it is to not go kablooey in the next second today.

At an individual atom level, radioactivity isn’t predictable. But, if you take a large number of atoms of one of these three isotopes (or of any unstable isotope for that matter), you can make some predictions.

You can say, for instance, that any large sample of uranium-235 will be half gone in about 700 million years. Half of the atoms (no way to predict beforehand which specific ones) will have decayed to something else. Does that mean that the other half will decay in another 700 million years? Absolutely not. If you start with a pound sample of uranium-235, after 700 million years, you now have a half-pound sample of uranium-235, now mixed in with a bunch of impurities to be sure, but a half pound sample nonetheless, and half of that sample will decay in the next 700 million years.

700 million years is the half life of uranium-235. Similarly, uranium-238 has a 4.5 billion year half life, and thorium-232 comes in at 14 billion years.

You get one guess as to who discovered the concept of a half life in 1907. I’ll give you a tiny hint: He did it using one of the short-lived isotopes in the thorium decay chain, one that was deposited by decaying radon gas.

Thorium-232’s half life is about three times that of uranium-238. As you can imagine, given a godzillion uranium-238 atoms, and a godzillion thorium-232 atoms, you’ll see three times as many decays in a day from the uranium as from the thorium. But it also scales by quantity; two godzillion thorium-232 atoms will produce twice as many decays in a day as one godzillion will. And three godzillion thorium-232 atoms will produce as many decays in a day as one godzillion uranium-238 atoms. Keep this in mind–the ratio of the half lives is same as the ratio of quantity, for the same number of decays to occur from samples of two different isotopes.

[A “godzillion” is a highly technical word someone made up once for a really large number. He used it to describe the national debt when it was a lot smaller than it is now. However, even today’s national debt pales next to the number of atoms in a mole (which would be 600 sextillion or so). I decided to adapt the term rather than just say “zillions” or “jillions.”]

When an atom of (say) thorium spits out an alpha particle, it actually changes to another element and another isotope; it is decaying. If the new isotope is also unstable, it too will decay, again and again until the result is a stable nucleus. Eventually the starting thorium-232 nucleus will have become a lead-208 nucleus.

OK, with thorium being Z=90 and lead being Z=82, we can do a little bit of accounting-style sleuthing. The difference between these two masses–the change in A–is 24. That’s the equivalent of six alpha particles. In fact, since the only mode of decay that changes an atomic weight is alpha decay, we expect exactly six alpha decays to occur during this process.

But going from thorium to lead would involve changing Z by eight, which is something you’d get from four alpha decays at two apiece. Six alpha decays, absolutely required by the mass change, give you a reduction of Z by 12, and so it looks like you’d end not with lead-208 but rather platinum-208 (which if it even exists, surely isn’t stable).

Beta decays come to the rescue. They move you one element to the right, without changing the mass. So if you figure that the total number of alpha decays is six, reducing Z by 12, but then throw four beta decays into the mix, increasing Z by four, it balances; the net reduction of Z is 8. The total set of reactions boils down to:

Thorium-232 (Z=90, A=232) – 6 alphas (Z=12, A=24) – 4 betas (Z=-4, A=0) = Lead-208 (Z=82, A=208).

(Remember when subtracting the four betas, you are subtracting a negative number, which means to add the opposite positive number.)

If you look at the detailed sequence of events, this is exactly what happens. Thorium-232 decays by alpha particle to radium 228 (Z=88, A=228 one alpha decay so far). Radium-228 then undergoes a beta decay to get actinium-228 (Z=89, A=228, alpha, one beta so far). Actinium-228 undergoes another beta decay to get thorium-228 (Z=90, A=228; one alpha, two betas so far).

Let’s pause here to look at the half lives. The original thorium-232 has a fourteen billion year half life. That means that (on a percentage basis) very, very little of it decays in (say) one day. The radium-228 has a 5.7 year half life. The actinium-228 has a 6.1 hour half life. The thorium-228 has a … wait for it! … 1.9 year half life. (It’s thorium, but it’s not thorium-232 and that makes all the difference in the world when it comes to half lives.)

If you started with a pure thorium-232 sample and waited about ten years, a certain amount of radium-228 has accumulated. As it accumulates, you can detect more and more decays of it (because there is more and more of it over time. But it won’t accumulate forever: It turns out that after a few years of building up, there’s now enough of it that it’s decaying about as fast as it’s being created. So you should be able to see based on our discussion above that, given thorium-232’s half life is three billion times as long as radium-228’s, when there is one radium-228 atom for every three billion thorium-232 atoms, then they’ll both produce the same number of decays. But the radium-228 doesn’t go away, because it’s being replenished by the thorium-232 decays. Since the amount isn’t changing over time the radium-228 is in equilibrium with the thorium-232. (The thorium-232 is slowly going away, of course, as it does so it will produce slightly less radium-228 during a given time, so the radium-228 will decline at the same percentage rate. But people don’t live long enough to see this happen, not with a 14 billion year half life!) Equilibrium is reached in something like 1 1/2 or two half lives of the daughter isotope.

Similarly for the actinium-228–because it has a much shorter half life than radium-228, it reaches equilibrium with the radium-228 almost instantly. And so on down the chain. Once everything is at equilibrium, there is one decay of each daughter isotope, for each decay of a thorium-232 atom. This is why a “pure” sample of thorium actually grows more radioactive right after it’s made.

So back to that chain. It continues. Thorium-228 alpha decays to radium-224 (Z=88, A=224, two alphas, two betas so far). Radium-224 alpha decays to radon-220 (Z=86, A=220, three alphas, two betas so far). Radon-220 alpha decays to polonium-216 (Z=84, A=216, four alphas, two betas so far). Polonium-216 alpha decays to lead-212 (Z=82, A=212, now five alphas and two betas so far).

Lead-212 is lead, and lead dug out of the ground is stable, but lead-212 is not stable. It’s an unstable isotope, a very unstable one in fact. Its half life is 10.6 minutes.

The next step is a beta decay, lead-212 becomes bismuth-212 (Z=93, A=212, five alphas, three betas). We now have just one alpha and one beta decay left to get to lead-208. But now, the path splits. We can either do the alpha decay first then the beta decay (thallium-208 (Z=81), then lead-208) or the other way round (polonium-212 (Z=84), then lead-208).

All of these decays from thorium-228 onwards have half lives of days or less, one even has a half life of less than a millionth of a second. So once the thorium-228 reaches equilibrium with its great-grandparent thorium-232, the rest of the chain ends up in equilibrium in just a few days.

The diagram below summarizes this whole process. And it uses a notation I haven’t used yet. So far when I’ve named an isotope, I’ve done it as [element name]-[mass number]. But you can also use a superscript before the element symbol like this: 232Th. Superscripting is a bit of a pain in the ass in the WordPus editor (and besides you might not know all the symbols), so I didn’t do it this way. It can even be taken a step further (and is, in the diagram below). You can put the atomic number Z as a subscript before the symbol, like this: 90Th. (Or you can do both. And I do mean you can do both. I can’t. If I try, I get something like this: 23290Th. I can’t get the super and subscripts one over the other.)

Technically the atomic number is superfluous, thorium is by definition atomic number Z=90. But it’s helpful for all the non-geeks out there who don’t have the numbers memorized.

(Even chemists don’t usually know all of the atomic numbers, nor do they know all of the symbols; I watched one give a lecture on this very sort of thing, and when he showed the symbol Pa, he called it “palladium” (it’s actually protactinium, atomic number Z=91; palladium’s symbol is Pd and its atomic number is Z=46 and its price is almost three thousand dollars an ounce. The symbol was right, his verbal reading was wrong). Chemists will know the common elements like sulfur (16, S), plus ones they themselves are personally working with…unless they’re complete geeks, in which case they’ve memorized them all. By the way, if you ever run into someone claiming to be an organic chemist and they don’t know that carbon’s atomic number is Z=6, he’s a faker. Actually, he’s a lying sack of bearded dragon shit. Run, do not walk, away, from this person, and do not believe him if he tells you that the sky is blue; don’t even believe him if he says that Joe Biden lost.)

One last thing to note about the thorium decay series. Every single isotope on it has a mass number A that divides by four. The starting number divides by four, and any time the mass number changes, it changes by four, so it will always be divisible by four.

The other two decay series have uranium in them. Uranium has two long-lived isotopes, and they are each at the beginning of their own decay chains. You can walk through them if you so desire, but I’m just going to put up the diagrams. The first is the “Uranium decay series” starting with uranium-238:

Every one of these isotopes’ mass numbers, when divided by four, leaves a remainder of 2. Therefore, none of these isotopes appears in the thorium decay series, and none of these appear there either. Never the twain shall meet.

Note that one of the intermediates is uranium-234 with 245,000 year half life. If you (personally) start out with pure uranium-238, you won’t live long enough to see it come into equilibrium with its daughter isotopes, because uranium-234 decays too slowly. Over about the next half million years, 234U will build up in the sample and then be in equilibrium. Everything downstream from it is much faster. You will see, rather quickly, the intermediate thorium and protactinium 234 isotopes reach equilibrium, though.

The uranium-235 series is actually called the “actinium decay series” to avoid confusion with the other uranium decay series. It includes the longest-lived actinium isotope, actinium-227.

All of these isotope mass numbers, when divided by four, leave a remainder of 3. They therefore won’t appear in either of the first two series, or vice versa.

There ought to be a fourth series, one where all the mass numbers leave a remainder of one when divided by four. Right?

Well, there was. A long time ago. The problem is no isotope in that series (which we can reconstruct today since we can make artificial isotopes) has more than a 2,140,000 year half life. That’s much shorter than the uranium and thorium isotopes in the other series. That isotope is neptunium-237 (Z=93). One of its daughters is uranium-233, with a half life of 159,200 years. Everything else in that series is shorter, much shorter.

If there was any neptunium-237 on earth when it first formed, ten half lives (21.4 million years) would have reduced it to 1/1024th of its original amount. Another ten half lives would have reduced it to less than a thousandth of a thousandth, or less than a millionth of the original amount. A total of eighty half lives would be enough to reduce an entire mole of neptunium to less than one atom on average, an undetectably small concentration, especially since the neptunium probably started out as a minor constituent of whatever rock it was in, to begin with. (Realistically, fifty half lives is probably enough to escape detection by modern equipment.) Seventy half lives is about 170 million years.

There was either never any neptunium-237 when the earth formed, or the earth is at least 170 million years old. In fact, there are a lot of isotopes with even longer half lives (like plutonium-244, half life roughly 80 million years) that do not exist in nature, and the same logic applies: either that isotope was never around, or the earth is hundreds of millions of years old, or even older–plutonium-244’s absence implies billions of years.

Returning to the “neptunium decay series,” because it has no sufficiently long lived isotope, it is extinct. When we started making isotopes artificially, we eventually found neptunium-237, and uranium-233, and all the others, and could then figure out what the neptunium decay series looked like. But back in the 1910s, this was all well in the future.

[Actually, oddball nuclear reactions sometimes create a trace of these isotopes in uranium ore, but that’s an almost immeasurable trace, and clearly not remnants of an original stock.]

The second to last product of the neptunium decay series is bismuth-209. It was long thought to be a stable isotope, but fairly recently it was discovered to have a half life of 19 quintillion years-almost a million years for every dollar of our national debt. It is so weakly radioactive that it might as well be stable, and its radioactivity is consequently almost impossible to measure. When it bestirs itself to do so, it decays to thallium-205, which is unfortunately quite stable. I say unfortunately, because thallium is extremely toxic. There is actually plenty of thallium-205 out there already, but it has to almost all be original or primordial stock, because hardly any bismuth-209 has decayed in a mere few billions of years.

Summing it up

Radioactivity was discovered in 1896. At that time, the words electron and proton didn’t exist. Atoms were indivisible things. Twenty years later, we knew that last bit was wrong, and we were well on our way to knowing the real nature of matter. In large part thanks to Ernest Rutherford.

OK. Next time, we take one step out, back into the realm of the electrons.

Obligatory PSAs and Reminders

China is Lower than Whale Shit

Remember Hong Kong!!!

中国是个混蛋 !!!

Zhōngguò shì gè hùndàn !!!

China is asshoe !!!

China is in the White House

Since Wednesday, January 20 at Noon EST, the bought-and-paid for His Fraudulency Joseph Biden has been in the White House. It’s as good as having China in the Oval Office.

Joe Biden is Asshoe

China is in the White House, because Joe Biden is in the White House, and Joe Biden is identically equal to China. China is Asshoe. Therefore, Joe Biden is Asshoe.

But of course the much more important thing to realize:

Joe Biden Didn’t Win

乔*拜登没赢 !!!

Qiáo Bài dēng méi yíng !!!

Joe Biden didn’t win !!!